As I’ve exposed in a previous post the term HEMA does not come with a good description of the goals or an exact prescription of the approach. The study of historical European martial arts can use a variety of methods, and depending on the goals of the student the activity can take different forms. There does not have to be a universal agreement on that, at some point it’s just different strokes for different people. The rest of this post is just a clarification of my personal views on these topics (and I much needed that clarification myself!).

I think my interest in HEMA was born from my interest in swords. At some point I felt that in order to understand these objects, you have to understand how they were used. Written sources are invaluable because they contain some of that original knowledge, which helps understanding how people back then thought swords had to be used. This does not have to be the most efficient way to use a weapon, by the way. For me historicity trumps efficiency, firstly because our efficiency tests are never entirely accurate, and secondly because I see no point in being efficient now: the weapon is obsolete, none of us is realistically intending to use it in earnest. It’s really what people thought was efficient which offers insights as to to how the weapon was designed. What they believed, why they believed it, how they structured their presentation of the art, that’s what I want to study on the theoretical side. This can dig very deep into the technological, social and cultural contexts, of course.

On the other hand, what do I get from martial arts training? First, the raw kinesthetic pleasure of swinging swords or sticks. Second, something which makes martial arts especially compelling to me, moves have meaning. Not only do the actions have a specific purpose, they are also associated to very high stakes, all the more so in weapon-based martial arts which are often matters of life and death. These two things get me to train. Training in turn has two positive side-effects: I get some measure of fitness which is good for my health, and I suppose I become a better fighter. The second thing is actually of little interest to me, as I don’t consider it relevant in modern society, except maybe in the psychological sense. By coincidence, just as I finish writing this, Guy Windsor publishes a relevant post! This is a nice description of the aspects that are specific to martial arts training as opposed to other sporting activities…

What makes HEMA special is that the physical training advances your comprehension of the technical sources, and that your study of the sources give you things to try out in your physical training. That feedback loop is especially attractive to me, maybe because it takes the meaningfulness of martial moves a notch higher: you have an almost direct contact with people who experienced their implications in a much closer way. That relationship to sources is indispensable to me; I would not get the same experience from a modern person explaining how he sees things or how I should move. I trust the sources much more than anyone’s interpretation, including mine of course.

For me the best physical display of HEMA is to demonstrate as accurately as possible the contents of the sources. This means to perform the moves with the necessary distance, timing, force, control and posture, and be able to link them back to the sources. This is not as easy as it seems! First you have to build a sufficiently precise interpretation of the sources, and then you can be as demanding as you want; in many traditional arts people train years to just perfect form like that, without having to interpret texts in the first place. This perfected display of historically sourced moves has to be reached before being able to perform at that level in freeplay or competition, assuming that the moves lend themselves well enough to that context of application, which is not certain at all. Hence I am making the historical moves my primary goal on the physical side, and their application in freeplay only secondary. That said, freeplay remains an essential (and fun!) part of the martial experimentation necessary in HEMA.

Here are two very good videos by HEMA scholars showing the sort of work I mean:

Interpretation of plates (and accompanying text of course) appearing in Salvator Fabris’ treatise (1606), by Žoldnieri Bratislava

Forms pulled from Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s 1572 work Dell’Arte di Scrimia by Ilkka Hartikainen

(Of course I’m referring only to the contents of the videos, not implying that these people’s approach of HEMA is the same as mine)

Ideally these display should be supported by scholarly works (presentations, articles, etc.) detailing how the interpretation has been built, from which sources, what are the parts that have been inferred through modern experimentation, in short the sort of information that can neither be conveyed nor argued by a physical performance alone.

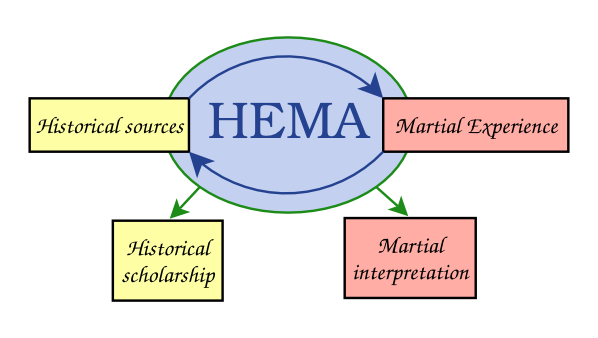

To conclude, here is my approach in a nutshell: HEMA is a feedback loop between experimentation in martial arts and historical studies of technical sources about personal combat. This results in heightened understanding both of the sources and of the physical and psychological aspects of combat. This understanding will manifest itself through the thorough knowledge of sources and historical contexts, and through the physical performance of an interpretation of the technical content.

A representation of HEMA as a feedback loop between historical sources and martial experience, resulting in historical scholarship and martial interpretation

“I get some measure of fitness which is good for my health, and I suppose I become a better fighter. The second thing is actually of little interest to me, as I don’t consider it relevant in modern society, except maybe in the psychological sense. ”

Ah, but it does. This is an integrated martial art that includes hand, knife, sword, etc. All these movements give you confidence and skill in a real fight. The only weapons these traditions lack are handguns and long guns; such training is available in the US and other countries. People get attacked all the time all over the world, regardless of a country’s laws, and learning this art gives the practitioner some skill in personal defense. It should be taken seriously because it may be needed on the street.

Yes it can be relevant, but not in the way it was in the past, and it has to be adapted to the modern context. If I were a noble (not necessarily rich or powerful) in the 16th century France, I’d pretty much expect to have to defend my life with a sword (against a sword!) at some point. In the modern society this would be a freak accident. I’m not training towards that goal. I get it as a side-effect. I take the arts seriously for different reasons.

In my opinion if you want training for a modern fight, there are more direct ways than studying relatively obscure texts about arts that were applied in a markedly different social and technical context. For example wrestling and knife defence are of course still relevant, and precisely for this reason there are living traditions for these. Learning from them will be hugely more efficient if you want to become a better modern fighter.

As one who is an instructor ijn a modern form of Ju Jutsu with old links, practitioner of Arnis and of modern hand to hand systems, training in HEMA as an adjunct or suplementary practice is very benificial to your modern defensive skills, mindset and perspective.

Use a sword? Carry a simple, stout cane and your sword work can be very relivnt to surviving an assualt.

But if all you do is get in good shape, a better idea of people before us and you have fun, it’s a win and a worthwhile practice.

I am enjoying your page very much.