With many countries under lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic, people are looking for ways to clear the heads and keep training. This gave birth to a very nice initiative: the Online Bolognese Form Tournament. The idea was to pick one of the various solo drills (assalti or abattimenti) described in the Bolognese sources, let people study it for 10 days, film themselves performing it, and pick a winner! With a good pick for the challenge, the competition was a considerable success: 50 contestants submitted their interpretation. I’m writing this post as a sort of training log for me to remember the choices I’ve made and the future work I would have to do.

I have written the rest of this post before seeing judge feedback or competition result. In all likelihood the feedback might change my interpretation, objectives and perception!

The abattimento

The organizers made an excellent pick for the challenge: the beginning of the part about sword alone in Marozzo’s book 2. This is in chapters 95 and 96 – or 94 and 95 in the reference translation provided, from Jherek Swanger (slightly edited to add headings with the same numbers as the original):

Cap.95. Elquale tratta dello abattimento di spada sola, da persona a persona

Hora guarda che io voglio che tu t’assetti in coda longa e stretta, con il piè dritto inanci e ‘l manco acconciato per di drieto al dritto, e la man manca de drieto alla tua schina e ‘l braccio della spada disteso forte inanci per lo dritto del tuo nimico; e de lì tu urtarai de uno falso filo tondo per la faccia al tuo nimico, con un mandritto fendente insieme, el qual fendente calerà a porta di ferro larga, crescendo in tal tirare del tuo piè dritto inanci; e se all’hora el tuo nimico te tirasse per testa o per gamba, in tal tempo che lui tirerà, tu urterai de uno falso de sotto in suso per la man della spada del ditto tuo nimico e sì li segarai d’uno fendente traversato per la faccia arredopiato, cioè tu ne tirerai dui a uno medesimo tempo: la gamba manca caccierà la dritta inanci e la tua spada calarà a porta di ferro larga.

Essendo in la detta porta di ferro larga e ‘l tuo nimico te tiresse una stoccata o uno mandritto per testa o uno roverso, a ciascuna de queste botte voglio che tu urti del falso della spada tua in la botta sua che lui tirerà e, in tal urtare, tu passerai uno gran passo del tuo piè manco inanci, inverso alle parte dritte del nimico, e in questo tal passare tu gli darai de uno roverso sgualembrato, che pigliarà dalla testa infino alla ponta delli piedi;

& per tuo reparo tu butterai il piè manco uno gran passo de drieto del dritto e, in tal buttare, tu li tirerai de uno mandritto traversato per el braccio della spada sua, el quale calerà a porta di ferro stretta; e de lì tu farai una meggia volta di pugno e sì te assetterai in coda longa e stretta, come di sopra te dissi, pure con il tuo braccio della spada ben disteso per lo dritto del ditto nimico & la gamba manca acconciata come di sopra.

Cap. 96. El qual tratta della seconda parte.

Hora, essendo rimaso in coda longa e stretta e ‘l tuo nemico fusse ancora lui in questa medesima guardia, overo che lui fusse in coda longa & alta, de lì voglio che tu cresci con il piè manco inanci e, in questo crescere, tu gli darai de uno falso impuntato, cioè tondo in la spada del ditto tuo nimico per de dentro, per modo che tu li segarai de uno roverso tondo per la faccia, crescendo a uno tempo medesimo del piè dritto tuo inanci; ma sappi che per tuo reparo tu butterai il piè dritto de drieto del manco: in tal buttare tu tirerai de uno altro roverso sgualembrato de gamba levata, che calerà in coda longa & alta e lì serai patiente, cioè tu aspetterai el ditto nimico che te tire, sicchè nota.

Cap.95. About the assault of the sword alone, in single combat

Set yourself in coda lunga e stretta with your right foot forward and your left one drawn near but behind it, your left hand behind you at your back, and your sword arm extended well forward straight at your enemy. From here, throw a false edge tondo to your enemy’s face, followed by a mandritto fendente that will fall into porta di ferro larga, stepping forward with your right foot as you throw that blow. If your enemy then attacks your head or leg, hit him in his sword hand with a rising falso in that tempo, and then slice his face with a fendente traversato, redoubled (which is to say that you’ll throw two of them in the same tempo) and make your left foot drive your right one forward as your sword falls into porta di ferro larga.

Being in porta di ferro larga, if your enemy throws a stoccata or mandritto to your head, or a riverso, in response to any of those blows, hit them with the false edge of your sword, taking a big step forward with your left foot toward your enemy’s right as you hit his blow, and as you step, throw a riverso sgualembrato from his head all the way down to his toes.

Then, for your safety, take a big step backward with your left foot, behind your right one, and as you step back, throw a mandritto traversato to your enemy’s sword arm that will fall into porta di ferro stretta. Then make a half turn of your hand and assume coda lunga e stretta like I told you above, likewise with your sword arm well extended straight toward your enemy, and your left leg arranged as above.

Cap. 96. About the second part of the assault

Being in coda lunga e stretta, if your enemy is in the same guard or in coda lunga e alta, then advance with your left foot, and in that advance throw a falso impuntato, that is, tondo, into his sword, on the inside, so that you can slice him with a riverso tondo to the face, advancing with your right foot in the same tempo. Then for your safety send your right foot back behind your left one, and as you send it back, throw, with a raised foot, another riverso, sgualembrato, which will fall into coda lunga e alta. Then you will be patient, waiting for your enemy to attack.

This was a very good choice because the weapon set is the most basic, with no companion, the abattimento is relatively brief, yet (Marozzo being Marozzo) retains some mystery in terms of vocabulary and more than enough room for interpretation. Therefore it was as the same time stimulating and accessible!

Interpretation

General principles

I have a sort of order of priority when doing that kind of exercise, which is something personal:

- Fit the text: any element of the text should find its way into the execution. The text is supposed to be complete unless this leads to contradictions, so no addition of unspecified footwork or bladework

- Cuts are cuts: they should be done with enough speed of the blade, correct alignment, along a flat trajectory. This might be overkill for some actions, but I feel it is a good goal to set

- Crispness and control: This is something I aspire to and have admired in all my martial arts masters. Body parts and blade should land where they should without imprecision or lack of unity. Balance should be maintained. Postures should not be unsettled by the impetus from strikes and steps.

Step by step

Let us take this in order. First the initial position:

TranscriptionHora guarda che io voglio che tu t’assetti in coda longa e stretta, con il piè dritto inanci e ‘l manco acconciato per di drieto al dritto, e la man manca de drieto alla tua schina e ‘l braccio della spada disteso forte inanci per lo dritto del tuo nimico;

Set yourself in coda lunga e stretta with your right foot forward and your left one drawn near but behind it, your left hand behind you at your back, and your sword arm extended well forward straight at your enemy.

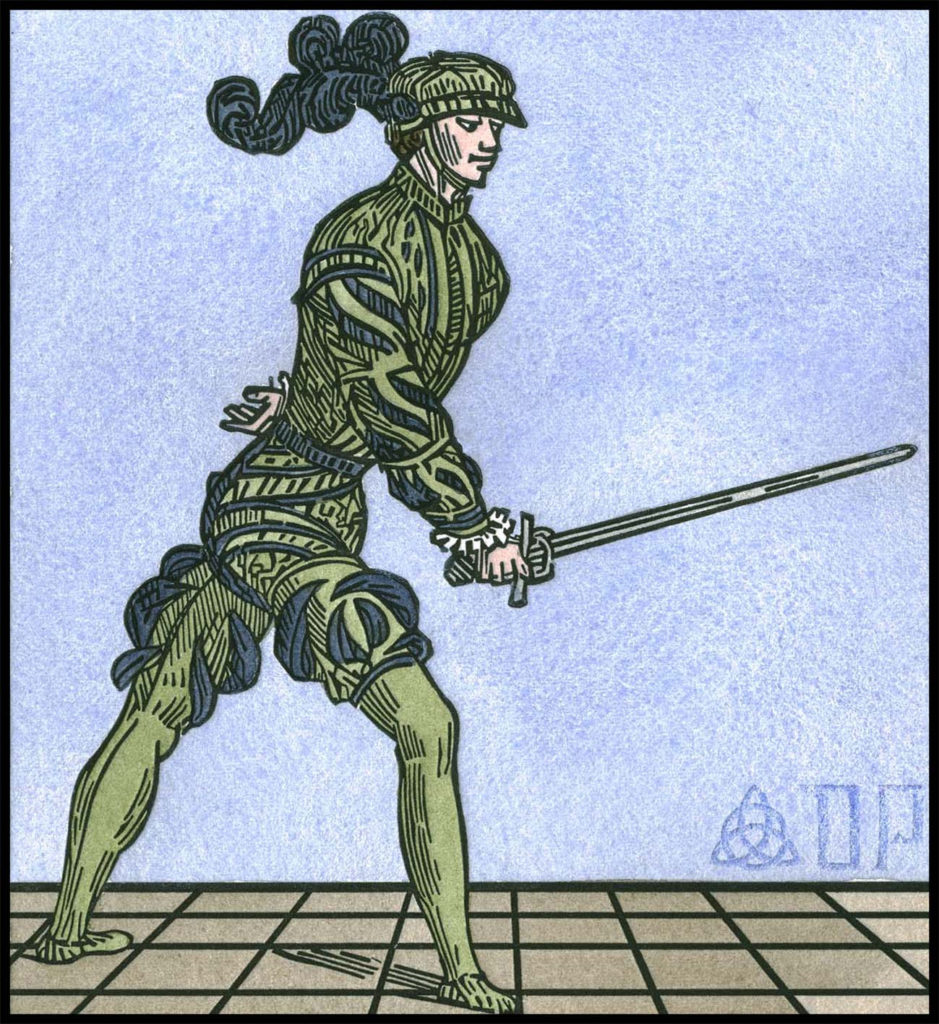

This is fairly straightforward, with the only difficulty being the position of the left foot: ‘near but behind it’ in this translation. I would guess it means ‘not quite in a wide stance’, and this seems consistent with the footwork following. The arm is specified as being extended forward, which is at odd with the guard’s depiction, and I’m not sure how to interpret it. I wouldn’t rule out the existence of several variations of this guard, and I consider that the defining factor is the hand position outside and near the right knee and the tip pointing towards the enemy, with body aspect and stance width being somewhat flexible.

From here, throw a false edge tondo to your enemy’s face, followed by a mandritto fendente that will fall into porta di ferro larga, stepping forward with your right foot as you throw that blow.Transcriptione de lì tu urtarai de uno falso filo tondo per la faccia al tuo nimico, con un mandritto fendente insieme, el qual fendente calerà a porta di ferro larga, crescendo in tal tirare del tuo piè dritto inanci;

The way I see it, this is a long-range provocation whose objective is primarily to set yourself in motion and dynamically reach a guard that gives some incentive for your opponent to attack. Therefore neither the falso nor the fendente are supposed to actually hit anything. The falso tondo is a big obvious flash above the sword to the opponent’s eyes, and the fendente is primarily a descent into the invitation in porta di ferro larga. Distance is not much broken.

If your enemy then attacks your head or leg, hit him in his sword hand with a rising falso in that tempo, and then slice his face with a fendente traversato, redoubled (which is to say that you’ll throw two of them in the same tempo) and make your left foot drive your right one forward as your sword falls into porta di ferro larga.Transcriptione se all’hora el tuo nimico te tirasse per testa o per gamba, in tal tempo che lui tirerà, tu urterai de uno falso de sotto in suso per la man della spada del ditto tuo nimico e sì li segarai d’uno fendente traversato per la faccia arredopiato, cioè tu ne tirerai dui a uno medesimo tempo: la gamba manca caccierà la dritta inanci e la tua spada calarà a porta di ferro larga.

The opponent has thrown an attack, but not a very commited one. We hit it away but we do not have enough of an opening to enter yet, so we follow-up with a variation of the first motion set that advances further, under the cover of the two fendenti. Two questions for this sequence:

- What is the foot-hand synchronization? Here we have three blade motions and two foot motions. It’s possible to do the falso firm-footed, and then do the two cuts and two steps (first left, then right) more or less in sync. This seems to be the implication of the text here, but it is not explicit

- How do we do the redoubled fendente, and what is a traversato cut? I have not seen much evidence for a precise technical meaning. I take it to mean that the cuts traverse the opponent’s figure without actually making contact. The first fendente is straightforward from the left to right falso, I have found it more natural to loop to the left to make the second one; this is analogous to the motion I’d make to throw two diagonal mandritti in succession, although arguably in the fendente case it turns the second one into something like a roverso fendente

These two phases more or less make up an entry into play, and in the next we are really coming to blows.

Being in porta di ferro larga, if your enemy throws a stoccata or mandritto to your head, or a riverso, in response to any of those blows, hit them with the false edge of your sword, taking a big step forward with your left foot toward your enemy’s right as you hit his blow, and as you step, throw a riverso sgualembrato from his head all the way down to his toes.TranscriptionEssendo in la detta porta di ferro larga e ‘l tuo nimico te tiresse una stoccata o uno mandritto per testa o uno roverso, a ciascuna de queste botte voglio che tu urti del falso della spada tua in la botta sua che lui tirerà e, in tal urtare, tu passerai uno gran passo del tuo piè manco inanci, inverso alle parte dritte del nimico, e in questo tal passare tu gli darai de uno roverso sgualembrato, che pigliarà dalla testa infino alla ponta delli piedi;

This one is pretty classic, big falso to clear the attack and roverso to hit, on a pass. The one point of contention would be how far to your left you would step, and how far forward. For the roverso to hit from head to toe, I’m inclined to believe that some stepping to the left is preferable, but without a training partner it is hard to know how much.

Then, for your safety, take a big step backward with your left foot, behind your right one, and as you step back, throw a mandritto traversato to your enemy’s sword arm that will fall into porta di ferro stretta.Transcription& per tuo reparo tu butterai il piè manco uno gran passo de drieto del dritto e, in tal buttare, tu li tirerai de uno mandritto traversato per el braccio della spada sua, el quale calerà a porta di ferro stretta;

You do not want to stay there after hitting, so you fall back with a strike to cover yourself. This brings you back to the original line. Ideally I would want to almost bounce back from the previous step, with no interruption, as any delay is a risk. Again that mandritto is traversato, but ending in a stretta guard. Possibly this means to cross the opponent’s figure but not let the point drop?

Then make a half turn of your hand and assume coda lunga e stretta like I told you above, likewise with your sword arm well extended straight toward your enemy, and your left leg arranged as above.Transcriptione de lì tu farai una meggia volta di pugno e sì te assetterai in coda longa e stretta, come di sopra te dissi, pure con il tuo braccio della spada ben disteso per lo dritto del ditto nimico & la gamba manca acconciata come di sopra.

I have seen some interpret the turn of the hand as an ‘almost cut’ from porta di ferro to coda lunga. The way I see it it is rather just a smooth transition back to the original guard: there is nothing to hit, no sword to parry. We are not in a hurry there. This brings us to the next chapter.

Being in coda lunga e stretta, if your enemy is in the same guard or in coda lunga e alta, then advance with your left foot, and in that advance throw a falso impuntato, that is, tondo, into his sword, on the inside,TranscriptionHora, essendo rimaso in coda longa e stretta e ‘l tuo nemico fusse ancora lui in questa medesima guardia, overo che lui fusse in coda longa & alta, de lì voglio che tu cresci con il piè manco inanci e, in questo crescere, tu gli darai de uno falso impuntato, cioè tondo in la spada del ditto tuo nimico per de dentro,

This time we attack the opponent’s sword, presumably to beat it out of the way. I do not think the falso is a way to simply make contact here, because the next action would leave the opposing sword in place to hurt us. The chain of action makes rather more sense to me if this is a strong beating motion. One may wonder if the first falso tondo above could also be called falso impuntato. In order for it to work I suppose you would have to make it rather explosive. The amount of advance of the left foot would adapt to the distance we begin at; in giocco largo I tend to assume a rather wide distance, and it is easier to shorten your steps than make them larger. Stepping with the left foot here goes against the direction of the falso, but this can be compensated by opening the hip joint and pointing the toes to the left.

so that you can slice him with a roverso tondo to the face, advancing with your right foot in the same tempo.Transcriptionper modo che tu li segarai de uno roverso tondo per la faccia, crescendo a uno tempo medesimo del piè dritto tuo inanci;

The previous falso has loaded the sword to our left, chambering nicely the roverso. Again how much of advance to make probably needs to be adapted according to the distance.

Then for your safety send your right foot back behind your left one, and as you send it back, throw, with a raised foot, another roverso, sgualembrato, which will fall into coda lunga e alta. Then you will be patient, waiting for your enemy to attack.Transcriptionma sappi che per tuo reparo tu butterai il piè dritto de drieto del manco: in tal buttare tu tirerai de uno altro roverso sgualembrato de gamba levata, che calerà in coda longa & alta e lì serai patiente, cioè tu aspetterai el ditto nimico che te tire, sicchè nota.

Just like we did at the end of the first part, the foot that has just advanced bounces back to break distance and a cut covers our retreat. Now the exact form of this cut is interesting, and the translation here does not correctly identify the technical term. For this I must thank Aurélien Calonne, whose translation isolates roverso de gamba levata as a technique, which is indeed defined towards the end of the first book (Cap.34):

[…] In order for you to know what is a roverso de gamba levata, I will describe it here once and for all: I want you to throw a roverso traversato, fleeing with your right leg to the rear and not touching the ground before this roverso is thrown. And as you flee with it, you will throw something like a kick to the rear […]Transcription[…] acciocchè tu sappi che cosa si è uno roverso de gamba levata, io t’el specificarò qui per sempre mai: io voglio che tu tire d’uno roverso traversato, fugendo della tua gamba dritta in drieto e non la mettendo in terra per fino che non è tratto il detto roverso & quando tu la fugirai, tu tirarai a modo uno calcio all’indrieto […]

It just so happens that there is a very similar technique in French canne de combat, that can be seen for example in this video at 23s (watch out the yellow and black fighter, and do not blink! This is fast). It is not normally used to fly back, and the strike here is vertical, because of la canne’s specific rules, however it shows the initial action quite well. Such a footwork has two important properties, one obvious and the other more subtle:

- It removes the low targets from the opponent’s reach

- It leaves the upper body almost in place, so that your own reach is not diminished. The kicking leg provides counter-balance for the upper body

So I would argue that this is not just a roverso thrown while stepping back, but a roverso thrown almost in place while only the lower body goes back, before finally we settle back into coda lunga e alta.

Video

Enough talk, here is the video I came up with at the end of the week:

Of course, while watching my video, the submissions of other contestants, and writing this post, I have identified lots I’d like to change!

- My initial guard does not have the arm quite extended enough, and maybe I’d square the shoulders a little bit more

- The first fendente ends with the hand too far forward and the wrist too extended

- I would change the footwork on the second action: falso firm-footed, then a quicker chasing step as the two fendenti are thrown. This is the most notable change

- I think my tip goes a bit too far out of line for the covering mandritto traversato, it is also a bit too diagonal so I end up quite far to the left for a porta di ferro stretta

- The second coda lunga e stretta is better, but could also be a bit more squared

- My falso impuntato goes too high! Unless the opponent is holding his sword very angled up… It could also be more direct if the beat is to be successful. Basically it looks too much like the first falso tondo

- As a whole, this could use a bit more speed. Cuts are good enough but could be chained faster, and with more agile footwork. More practice would give more fluidity

Many thanks to the organizers and judges: Reinier van Noort, Jay Maxwell, Luca Dazi, Robert Rutherfoord and Richard Cullinan, and congratulations to all the contestants!