In last July, I ordered a new rapier: the Galante model by Malleus Martialis. My goal was to have a lighter rapier than my Darkwood, something less tiring to the arm which could be used more comfortably over long events, or more casually for a few minutes in the evening. This rapier seemed to fit that bill, although it is always hard to be sure without having the object in hand! It also had several apparent qualities that I will go over below. I had already bought the Achille targa from the same maker, and I was quite confident in the quality of their work.

The order process was really smooth. There has been an unfortunate delay but communication was always easy, responsive and kind, and the adjusted expected delivery date was respected. Malleus Martialis has a really good reputation in that regard, and it is well deserved in my experience: the targa order had happened in the same way.

The rapier was well secured and oiled in the packaging, which ensured a safe travel, and rather speedy considering the uncertainties due to the pandemic.

Design

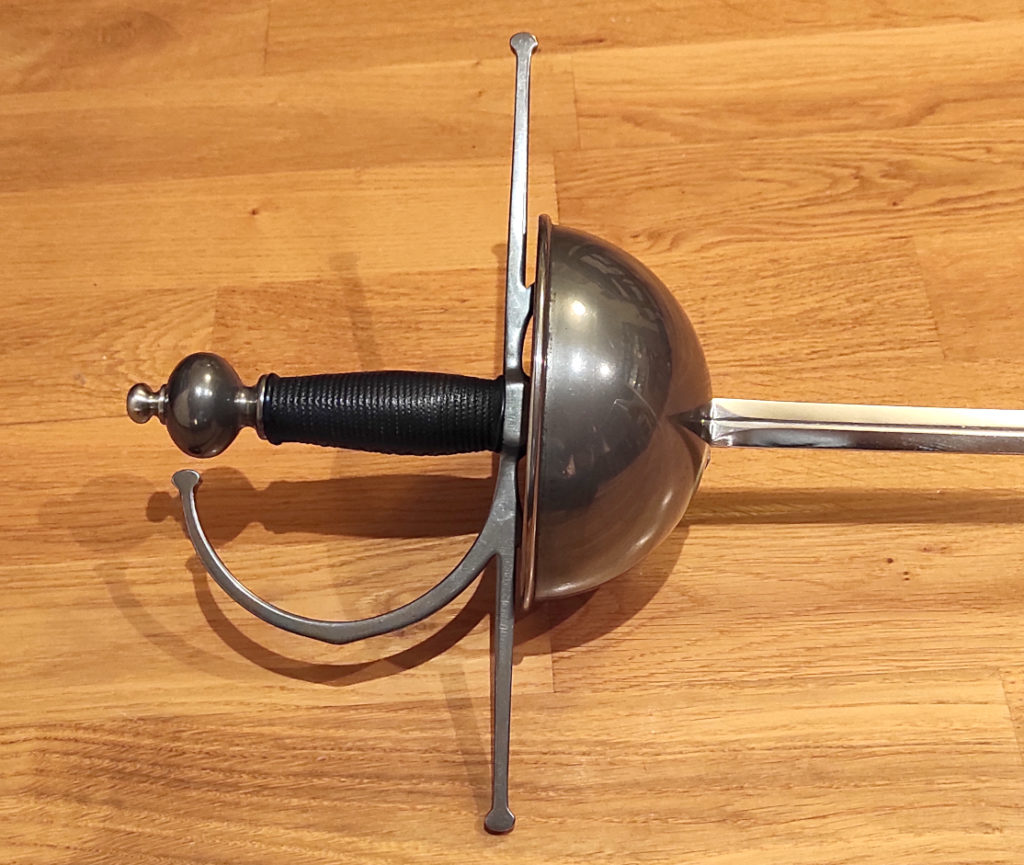

The Galante rapier is a cup-hilt with the following stats:

- Blade length (from junction cross-handle): 106.8cm

- Blade width at cup: 17mm

- Blade thickness at cup: 5mm

- Overall length: 120cm

- Mass: 945g

- Quillons span: 28cm

- Cup diameter: 13.5cm

- Handle length: 8.9cm from the quillons to the narrowest point towards the pommel (which technically is part of the pommel)

In themselves these stats are not exceptional for a cup hilt on the lighter side. What I am particularly happy with are the dynamics of the sword. Here is a comparison of the dynamic graphs of my Darkwood rapier and the Galante:

Of course the difference in overall weight is significant (the Galante weighs 14% less overall), but perhaps even more so is the difference in effective mass at the blade node: 40g shaved from the 190g of my Darkwood, more than a 20% decrease. This is definitely noticeable in the hand! Another important point is that the mass is more concentrated around the Center of Gravity, which can be noticed by either looking at the position of the pivot point associated to the blade node (in dashes towards the hilt) or at the position of the pivot point associated to the cross. This is actually more representative of the original rapiers that I have data about. It is a relatively small effect, but it is a nice to have, and something often missed in training swords, which inherently have more mass at the tip (which is blunt) and compensate that with a heavier pommel. It makes them heavy at the ends

, so to speak, and this rapier avoids this pitfall.

The flexibility is 4.2kg, compared to 4.9kg for the Darkwood. It is a bit more flexible, but because it is also a bit lighter, it is not floppier, quite the opposite in fact.

Another difference which the drawings here does not highlight enough is that the Galante has a shorter handle (by 0.5cm) and a shorter hilt overall (by 1.1cm). Again these might not seem much, however it makes a world of difference in handling, as the pommel does not get in the way at all.

I have personally measured a rapier in the Ecouen Renaissance Museum which is extremely close to this one in terms of size and dynamics, albeit marginally shorter and lighter overall. They are almost twins, in terms of dynamics! Both are a pleasure to hold and move with.

Construction details

The whole sword has an extremely careful and tight assembly. Nothing shows even a hint of a motion here. The sword is dismountable thanks to a hex nut at the pommel, but I have not tried it yet.

The cup is not resting on the quillons, which surprised me at first. It is in effect mainly supported by the arms of the hilt on the inside, to which it is riveted. The riveting seems quit solid, and the arms wouldn’t break, but I do wonder how well it would endure heavy cuts landing on the cup. Although I’m not sure how much the contact with the quillons would help, it would be one more point of support, which I think I have always seen used in historical examples.

The cup’s edge is safely rolled, rather than having the rompepuntas

which are also common on this hilt type (merely a wide turned edge made to catch the opposite tip). For a sparring weapon, it is the best choice in my opinion.

The handle sports a leather wrap. I might have preferred a wire wrap in absolute terms, but the handle shape is very correct and it is perfectly executed. Rapier handles do not get hit all that much and are not supposed to interact with rigid gloves, so I would expect this to last anyway.

The blade is particularly interesting in its conception, and I also wasn’t expecting this because I had not looked for that detail in the description. The two sides are not similar. On the outside flat, the blade has a central ridge with a narrow fuller on the strong. On the inside flat, there is a much wider and longer fuller, transitionning to a flat section from the blade node to the tip. In principle, it is not dissimilar to a smallsword or épée blade, still with two clear edges. It is an interesting solution to the problem of building a safe blunt rapier blade. A sharp blade could have the same balance with a more standard hexagonal section; that is the case of the Ecouen rapier I mentioned earlier. This cross-section choice lets the light blade be relatively wide, therefore keeping a feel of edge alignment, without making it so thin and flexible that it becomes too flexible and floppy.

The tip is swelled to about 5×5 millimeters. It still is quite narrow of course, but that is the expected compromise for such a light and well-balanced blade.

One thing I particularly like is the attention to detail in the finishing of the sword. It is apparent that the maker is looking at the ergonomy of the sword at every stage of the work. Not only are the proportions and lines beautiful to look at, but the finish is such that merely gripping the sword is a pleasure. There are no sharp edges left anywhere and certainly not under the fingers as one might find on lower-end rapiers. I had experienced that same quality of excellent design and execution in their targa, and the rapier is every bit as good as I wished for in that regard.

There is a unifying design intent behind Malleus martialis weapons which I find quite interesting. Their sport collection items are unmistakably modern: they are not trying to copy the visual aspects of originals in details. In the case of this rapier, the uniform squarish cross-section of the quillons, arms and knucklebow is not something I remember seeing on antiques. However, they do manage to capture very well the most important parts in my opinion: the overall proportions, the ergonomics, and the dynamics.

Conclusion

This training rapier has met or exceeded my expectations on all counts so far. Excellent dynamics and ergonomics, stellar finish, solid assembly out of the box. It really is the sword I wanted to get.

If a negative point had to be picked, it would be the gap between the cup and quillions for me, but I cannot even say how serious of a problem it actually could become in practice.

The big question mark that remains, and this is why I chose the title ‘Initial look’, is how it will age and endure the impacts of sparring. Of course due to that cursed pandemic, I expect it will be a while before I can truly spar with it. My gut feeling is that it would work well like vs. like, but I am not sure how it would cope with heavier rapiers and/or more violent opponents. One thing to note in this respect is that the hilt components have a special treatment that is meant to resist better to rust and impacts (not easy to show in photographs, but they are darker than the blade’s steel). I’m curious to see how it will react in time, with handling and cleaning. One thing for sure is that this sword will be a joy to fight with!

Not a comment per se, but I was wondering how this sword has held up since you’ve had it? Has the gap between the cup and the quillon been an issue?

Hello Brent,

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to use this sword as much as I would have liked: I mostly do rapier at events and Covid has put a hard stop to them since I got this one. Obviously, dry handling and thrusting drills are not a problem… Other people have reported problems under heavy use, though, with rivets coming undone. Malleus Martialis now offers hex screws instead, which can at least be tightened again.

Apparently the fact that the cup is hardened is what creates the whole issue. The hardening process makes it harder to precisely control the final size and therefore to make sure that the cup rests precisely on the quillons. At the same time, the hard cup does not deform to absorb blows, and instead transmits all the force to the rivets. It’s cool to have a hard cup, having it crumple is also a nuisance, but the unfortunate side effect seems to be that the rivets suffer.

Interestingly, it seems the historical cup hilts generally have screws as well in this place, so the fragility in this place must have been a problem back then too!