While they appear to be natural, cuts are among the most difficult moves to do well in swordsmanship. With historical blades, they require good synchronisation and involvement of the full body. They can be terribly efficient, and yet can fail in surprising ways when certain basic aspects are not performed well. Surprisingly, source documents appear to be quite terse on what was seen as an appropriate cutting technique. They generally refer to cuts as high-level actions without delving in the finer mechanical details. Almost certainly, the mechanics were taught by example first and foremost, along with the more or less universal basics of weapon use.

Many cuts occur along with some form of step to bridge distance. Mechanical low-level questions include:

- What part of the blade is used to cut?

- What is the motion of the blade in the target?

- What is the trajectory of the sword?

- Is there a specific order to the motions of the limbs?

Modern experimentation and physics can bring insights on these topics, and will hopefully be the topic of further posts. That being said, I believe it is important to use the sources to the fullest extant possible, because they bring us the authentic historical point of view. If we don’t perform cuts as they thought they should, then our understanding of both cuts and counters against cuts will be biased.

In this post, I want to share quotes from source texts and a selection of images that I am currently using to inform my cutting mechanics. I will focus on the low-level aspects listed earlier; the tactical use and classification is much more variable from one author to another.

Which sources am I using?

For these questions, I am making the hypothesis that pulling from a wide array of sources is valid, up until we find contradictions. Some of the sources I know best are categorized as rapier texts. I know it will surprise some people to these in order to understand cuts; these authors show a marked predilection for the thrust and you could argue that the cut was not their area of competency. I argue the opposite; cutting swords were used all through this period, and even thrust-oriented rapiers had a menacing cutting capability. Furthermore the authors talk plenty about cuts, use terms and diagrams that were in use before the rapier heydays, and Alfieri for example illustrate cuts as an alternative to many of his actions. These texts are also well-written, precisely illustrated, and focus on the basics in a way earlier texts do not.

The notions that people could not cut well in the later period is I believe put to rest by this quote taken from a text about fencing with sword and cape. In this weapon combination, the cape is wrapped around the left arm; a portion of it is left hanging down and is used to parry thrusts thanks to the weight of the cloth. It can also be used to bind the opponent’s weapon more securely. Fabris warns us:

As you parry a cut, you should never put your [left] arm in harm’s way, since the opponent could cut through the cape and wound you. Even if you were to wrap the cape completely around your arm, you may still be unable to oppose a cut without injury to your arm […].

Salvator Fabris, Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme, trans. Tom Leoni

In other words, it was fully expected that a cut might wound you through several layers of heavy cloth wrapped around your arm. That seems quite respectable enough to me!

Texts

Texts are the part of sources that we should trust the most. They were supposedly all written by people who knew about the topic, which is not always the case with illustrations.

The importance of slicing

Italian texts underline the necessity of having a slicing component and using the weak of the blade, but not the tip:

[…]when executing a cut it is better to perform it half with the third and half with the fourth part [of the blade]; this way, the cut is twice as damaging as if it were delivered with the third part alone.

Salvator Fabris, Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme, trans. Tom Leoni

Although this might seem unclear, Fabris is not referring to striking squarely between the third and fourth quarters of the blade towards the tip. Rather, he is describing how the blade should slice through. Capoferro is clearer on that topic (not a common occurence!):

Cuts should be executed with a saw-like motion, thereby allowing the whole debole to perform the strike. Also, by doing so, the sharpest part of the blade is gradually brought to bear.

Ridolfo Capoferro, Gran Simulacro dell’Arte e dell’Uso della Scherma, trans. Tom Leoni

The slicing motion here is always a pull (this is consistent with the illustrations that I will show later). But there are references to push cuts in some texts (in the Bolognese school for example), so this is supported too.

Sequencing of motion

The issue of sequencing of motion, or how to use the full body to achieve the cut in a tactically sound fashion, is the hardest one to explore. Many modern HEMAists base their understanding on the theory first outlined for fencing lunges, a thrusting attack: first extend the arm then bend the body then step. I think it is misguided as a thrust is mechanically quite different from a cut. Some see the text from George Silver as a confirmation of this view, but the interpretation of that source is challenging and I don’t believe it actually supports the notion. I’ll leave that debate for another day, and focus on what the other sources tell us…

There are textual hints as to how the cutting motion (arming the strike, striking, recovering) syncs with steps. For example in Thibault:

While the sword and arm go up with a violent [as in Aristotelian physics, upwards] motion, yet with the body still stays far away in the first Instance; and when the sword goes down, the body advances and approaches, but this is done with the advantage of the natural [downwards] motion, which is suited to break and tame all the devices of the opponent.

Girard Thibault, Académie de l’Espée, trans. mine

This seems to point out that the strike is armed from a firm foot while still far away, and that then the cut descends as you advance. It does not cover you by bringing the blade in front of your body, but because of the impact it generates. Note that the cut starts from first Instance i.e. roughly one step away from the opponent.

Another text, not on rapier this time but about the montante, the Iberian two-handed sword, focuses more precisely on the end of the cutting motion:

And to better achieve this perfection in practice, it is necessary that the swordsman knows (as a universal rule) that all the blows of the montante have to be given such that the body is steady at the end of the natural movement [i.e. downward motion of the blade], which is the one used for offense, and the means of execution, because if the body is moved (since this weapon is used with two hands, and thus requires you to apply a certain force because of its weight) you could dangerously fall, either for not being well and firmly planted, or by missing, due to a deflection, the object to which you directed the effect.

Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo, Memorial Da Prattica do Montante, trans. Eric Myers

This indicates that the cut should reach the target after or as the foot settles down and the body stops moving forward. The reason stated is that if your body is still moving forward during recovery, it might unnecessarily expose you at a moment when you cannot use your sword for defense. Note that over the course of a step, it is impossible to stop the body without having the front foot down first.

Illustrations

Illustrations are very hard to replace when it comes to indicating precise body position, but reliable illustrations of cutting motions are few and far between. It’s only in relatively late works, starting at the end of the 16th century, that we start to see frozen frames that can be cautiously trusted. That trust is established by the respect payed to human proportions and anatomy, as well as the use of perspective that is indicative of a research of realism that is not present in all works, and not artistically possible in all periods either.

A little gem: the full strike from Thibault

Girard Thibault’s Académie de l’Espée is to my knowledge the only treatise showing four successive images of the same cut. It is found on the plate of table XI, in book 2. It should be of interest to the majority of HEMAists, as it shows a swing of a two-handed sword! The swinger is shown in the initial guard (a variant of the German Zornhut or Italian Posta di Donna), then as his body travels forward, then as the cut reaches full extension and the expected impact, and finally during the recovery phase.

As you can see on the right, the figures are not all of the same size. With the help of Thibault’s circles repeated under the feet of the pair of fighters, it is however possible to line up and scale the figures to create an animation! Of course this is not perfect; the models are not perfectly similar (the fourth person seems to have been a bit shorter) and you have to account for artists error and slight perspective problems from my camera lens. That said I do think it looks fine:

On the second and last image, the fencer is hit by a counter thrust, so conceivably these frames might be different from the true position, and the second frame is very much caught in the middle of a fast motion, which in 1628 must have been difficult. But that is the best representation of a full swing that we have to my knowledge.

Note that the weapon reaches full extension (the third stage) as the rest of the body comes to a stop. Only the sword and arm are moving during recovery. This is consistent with the Montante text. Also observe that the blade is slightly angled at the moment of intended impact, which creates some natural slicing effect, as described by the Italian authors. Finally, we have a fairly good idea of the trajectory of the cut here. The hilt follows an arc and does not cover the swordsman up to the middle of the step. Of course the arc is nowhere near as dramatic as in the croisé tête from la canne… But it is present.

Images from rapier texts

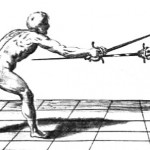

Thibault is original in his depiction of successive stages of the exact same cut, but other works contain frozen frames of cuts (though mainly being countered!) at various stages. Here is a selection of images sorted in the chronological order in which they would happen in a cut:

- A cut caught as it is chambered, or as it goes down, in Fabris

- A cut caught as it is launched, in Giganti. Note the foot in the air

- A cut caught as it falls, in Alfieri. Note the barely landed front foot, and hand still higher than the line of attack

- A cut caught at impact, in Fabris

- A successful cut, in Fabris. Note the lowered hand.

- A cut caught in the recovery phase, in Fabris

Although the weapon is not the same, they are remarkably consistent with the textual advice and with Thibault’s images. As the cut hits and during recovery, the feet are planted and the body moves very little. The weapon is angled, with the hand consistently depicted lower than the point of impact (these are all descending cuts). The hand is arching through the cut.

Conclusion

To sum things up, here are my take-away points, what I consider a “sourced” historical cutting mechanic:

- Arm the strike as far from the opponent as possible

- Strike with the weak of the blade, but not the tip

- Include a slicing motion

- Use an arching motion of the hand, such that it moves across the intended target

- Have the front foot down when the sword hits

It seems to apply to all sorts of weapons in the sources. I’ll keep being on the look-out for other hints in our sources, and in the meanwhile I’ll try to practice this!

Image credits:

- Thibault’s images are photos of my Kubik facsimile

- Fabris’ images selected from Fægtekunstens Venner

- Alfieri’s image from the Raymond J. Lord collection

- Giganti’s image from the Herzog August Bibliothek

Hi

Just wanted to say thanks for all the very good work on these posts. Great stuff!

Y

My pleasure 🙂

This is excellent, sir.

When I first started in HEMA (not long ago) I was told on a few occasions that the cut should always lead the body – that the sword always goes first. In practice I ended up sort of cutting first and then stepping – which feels strange to me. Review of modern examples online seems to show a mix of methodologies. I’m thinking particularly of tournament footage of Axel Pettersson which shows predominantly simultaneous step and cut. Keith Farrel on the other hand demonstrates a definite cut then step methodology during one of his classes on Kolner (Dreynevent 2014).

In short, I’ve been unsure. Your post is certainly a useful data point though, coming from historical sources. I’m probably many years of study/practice from being competent to have an opinion on the matter – but until then I’m comfortable defaulting to the sources.

I truly appreciate this sort of work and your sharing it publicly.

Thank you!

I’m glad this seems useful to you. I intend to explore that topic further from the tactical and mechanical standpoints (my article on Silver’s times was a preliminary for that). It is really rich! I don’t know when I will find time though 😉 But one day!

Regards,

We do have another example of the same strike in four positions, actually more. If you look at all the image starting with the Zorhaw the middle is referred to as just ‘oberhaw’ and ends in Alber. There are a few more strikes that are Krump and Schaitelhaw are also discernable, though not as much.

http://wiktenauer.com/wiki/J%C3%B6rg_Wilhalm_Hutter

Here is the Zornhaw:

http://wiktenauer.com/wiki/J%C3%B6rg_Wilhalm_Hutter#/media/File:Cod.I.6.2%C2%BA.2_06r.jpg

http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0006/bsb00064546/images/index.html?fip=193.174.98.30&id=00064546&seite=43

http://wiktenauer.com/wiki/J%C3%B6rg_Wilhalm_Hutter#/media/File:Cod.I.6.2%C2%BA.2_40r.jpg

http://wiktenauer.com/wiki/J%C3%B6rg_Wilhalm_Hutter#/media/File:Cod.I.6.2%C2%BA.2_14v.jpg

Hello Jesse,

I’m not terribly familiar with the early German stuff… If I understand correctly, here the positions are not contiguous in the text? That is, these are several guards and positions, but not necessarily described as belonging to the same cut? In Thibault, it is exactly the same cut depicted on several frames. It is true that it is possible to reconstruct other cuts in other sources, but I’ve never seen another source that depicts stages of a given cut, explicitly.