There is a trend in HEMA that seems to be rising these days: working at low speed, even in freeplay. It’s not a new idea, indeed most people have practiced like that at some point, but a stronger emphasis can be put on it. The tenants of this approach use that method for a variety of reasons. First it makes the practice safer, because the weapons cause less damage at low speed and the actions are more predictable, making it easier to control the strikes. It allows to demonstrate relatively complex sequences from the manuals, even for relative newcomers. Specifically, it makes actions from the bind show up with a far greater frequency. Finally, there is an idea that speed should not be a component of the art and that actions do not rely on speed to achieve their goals.

In this article I want to explore what the sources say about speed, and what distortions are provoked by the reduction of speed. I will share my personal (current) conclusion at the end.

Speed in the treatises

Direct recommendations

Speed is explicitly pointed out in the source treatises as a desirable quality for swordsmen. For example, Fiore dei Liberi (writing in the early 1400s) uses animal metaphors to expose the qualities of a fighter, and has this to say:

Celerity (Swiftness)

I, the tiger, am so swift to run and to wheel

That even the bolt from the sky cannot overtake me.Fiore dei Liberi, Flos Duellatorum, trans. Michael Chidester

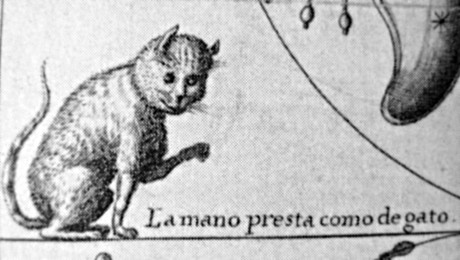

This trend continues quite late, and Miguel Perez de Mendoza y Quixada writes in 1675 that the swordsman needs to have ‘the hand quick as that of a cat’. Anyone who has been around these animals can attest that this is quite fast!

I find it hard to argue that speed was seen as unnecessary or a mere side-effect based on the texts. There are sources that point out that speed is not enough, but it is different. Something can be necessary yet not sufficient, to be honest most concepts in martial arts fall in that category.

Why do we need to be fast?

There are two main reasons pointed out in period sources.

The first is that sword cuts were meant to use speed to achieve their effects, the momentum of the sword being converted to very high forces upon impact. It could be argued that not much speed is actually needed to cause damage, but it is apparent that they did expect blades to travel so fast that there are references to sword blows breaking blades upon parries. Here in Viggiani again for example:

pay heed that in this delivering of the rovescio, the swords meet each other true edge to true edge, but that the forte [strong] of your sword will have met the debole [weak] of mine, whereby mine could be easily broken by virtue of the disadvantage of such a meeting, and also because of the fall of the cut;

Angelo Viggiani, Lo Schermo, trans. William Jherek Swanger

There are also warnings to that effect in Thibault which I ommit for brevity. Breaking a tempered steel sword in this fashion cannot occur with slow moves. The sword is not pushed or sliced through the target as a knife would be, but propelled at great speed so that its momentum provides a far greater pressure than could be exerted by the muscles (especially on the weak!) at slow speed. This method is observed as late as 1841 in Colonel Marey’s work:

In the cut, a sword should be considered in the light of a projectile, of which the portion in the neighbourhood of the point has a much greater velocity than the hilt. The hand gives it this impulse, and does not act by pressing the sword on the body to be penetrated at the moment of impact.

Colonel Marey, Memoir on swords etc.

The second reason speed was seen as necessary is that it allows to outpace the opponent’s reaction time, which is very relevant to feinting or generally hitting the opponent. George Silver illustrates this well when he discusses how the time of the hand is even faster than that of the eye:

For proof that the hand is swifter than the eye & therefore deceives the eyes: let two stand within distance, & let one of them stand still to defend himself, & let the other flourish & false with his hand, and he shall continually with the swift motions of his hand, deceive the eyes of him that stands watching to defend himself, & shall continually strike him in diverse places with his hand. […] He that will not believe that the swift motion of the hand in fight will deceive the eye, shall stare abroad with his eyes, & feel himself soundly hurt, before he shall perfectly see how to defend himself.

George Silver, Paradoxes of Defence, 1599

This is something that can only be done with speed. Anyone who ever played tag as a child can relate to that experience…

The conclusion of this exploration of source texts is that fencing moves are always supposed to be applied with as much speed as can be gathered (while keeping the needed control, of course), and that some do not work unless a certain threshold of speed is reached. It is therefore my opinion that any demonstration of historical fencing should be done above that threshold.

However, this does not mean that training at low speed is useless. The gains are obvious and are already argued elsewhere: increased safety, ease of stringing actions together, facility to achieve and keep blade binds. But to make the most of it one has to be fully aware of what it distorts, which I will discuss in the next part.

Distortions brought by low speed

What do you distort when you dial down your speed?

The most obvious thing is that you have less momentum and far less kinetic energy in the weapon and body. This is a good point for safety, but it also means that any actions that use momentum will not work as reliably or efficiently. For example, beats on a static blade, or impacting parries have to be performed at speed if they are to provide the opening or clearance needed for further actions. It is possible to compensate for that by acting very soft and relaxed on the receiver’s side but this is a hard discipline to stick to. Forces exerted through binds, on the other hand, are not modified. Depending on the actions trained, this will be more or less bothering, and a very bind-focused treatise like I.33 will be better suited to slow study than for example Bolognese works, where beats and impacts are very heavily used.

Gravity cannot be slowed down. As you move slow, you are still pulled to the earth just as much as if you were moving fast. This makes it impossible to move exactly in the same way, especially as far as footwork is concerned. When people walk slowly, they have to shorten their stride or modify their gait simply not to fall down. Running or jumping is even more problematic or downright impossible… Basically if you move slowly and only have one foot on the ground, you have to keep your centre of gravity above that foot or you will start to fall. At speed you are still falling, but you may well have time to set your other foot where it needs to be before falling over much of a distance. An example of a footwork situation which makes the effect obvious is again in the Bolognese works. When your forward leg is attacked, they point out that you can just retract that leg beside the other, let the cut pass and then put it back, using that void to simultaneously strike. When you do this slowly, you have to retract your body as well. When you do it at speed, you can move just your leg, and your body won’t move much before it comes back. Obviously this changes the reach of your sword, and hence the finer mechanical details. There are many other footwork sequences where the trajectory of the body has to be modified to work slowly, changing the measure or the angle, which are two very important parameters.

Low speed gives unrealistic expectations of how you might react and of the strength of certain defences. At low speed you can react during almost every action that the opponent makes. You can even consciously consider your options, even if you don’t make the right choice given the situation. This is totally unrealistic, as the Silver quote points out; certain motions occur too fast for us to react, especially when relying on visual perception. In these situations, low-speed work might make you think that you are safe, when you are in fact in great danger. Besides, the ability to consciously pick the right move is somewhat disconnected from the ability to pick it reflexively. At slow speed you validate the first one, at high speed the second one is what matters.

Conclusion

The application of the art was meant to be done at high speed. Speed is not a side-effect of training but rather one of the core objective. There is a saying that fast and wrong is still wrong, but slow is wrong too. Mechanical invariants such as gravity make it impossible to really be right and slow in our endeavour, just like you cannot learn juggling slowly.

In my opinion low speed work is essentially useful to roughly rehearse a sequence of actions in the very first stage of study or demonstrate static effects such as strong vs. weak in a relatively unmoving bind. It is ill-suited to the demonstration or experimentation of the finer mechanical details, because the lack of momentum and the distortions of footwork will interfere with them. In a freeplay environment, it takes a great deal of experience at high speed to remain honest at low speed, as far as reaction times are concerned. Although safety concerns can make lower speed necessary, I actually believe that for comparable safety a scripted full-speed drill will be more useful, both to become a better fighter and to better understand the mechanical and neurological effects that make the techniques work.

Great article, Vincent! It needed to be written.

Glad you liked it!

I like the article! As a fencing coach I believe that form should be taught slowly, almost like a kata. Once you have a solid grasp on the form, it’s time to practice it at full speed. The part where it gets really fun, (and by fun I mean difficult), is adding acceleration to the move. Being able to go from slow, to fast. Having your muscles go from loose, to tight. changing your tempo to disguise your intentions. That is when you are moving like a cat. Of course sparring with that kind of intensity is dangerous, but it’s the only way to know how to do it, or how to defend it….

This was a more interesting and more useful article than anything I have seen in the USFA magazine in years. Thanks for posting it!

– B

Thanks!

Yes acceleration can be a very useful tool and I have personally experienced its effects while training in canne de combat (both on the giving and receiving end!). But precisely, in order to use that tool you must have trained to perform fast as well as slow, and it works all the better if you manage to mimic your fast mechanics at a low speed (not always possible). So even in slow work I’d rather focus on mechanics that will remain sound at speed.