It is often tempting to draw links between authors of fencing treatises, even on extremely flimsy basis. One such link is the idea that the French master Henri de Sainct-Didier was in contact, or even influenced, a young Salvator Fabris. For some reason this claim has found its way to the Wiktenauer, and I hear it now with some regularity. But what is the validity of that claim?

When such claims are made, it is vital to check the elements of proof which accompany them. Unfortunately, in this case, there is basically no proof. It seems to all come from Arsène Vigeant’s Bibliographie de l’Escrime Ancienne et Moderne (1882):

A very curious note: taking into account that Fabris, born in 1544, was 62 years of age when the original edition of treatise was published in Denmark, in 1606, there are reasons to believe that the “Italian Fabrice”, who had with Saint-Didier the theoretical discussion that is reported in Saint-Didier’s book, in 1573, was no other than Salvator Fabris himself, who had to travel through Paris at about that time, in order to reach Denmark.

What these “reasons to believe” actually are is unfortunately left for us to figure out, beyond the phonetics!

The theoretical discussion starts like this in Sainct-Didier:

About the six points above, persons named Fabrice & Jule once came to me, with a few people from their country, because they had heard of me, & they were told that I was writing a book about fencing & that I had dedicated it to the King.

The object of the discussion is to know how many different sorts of attack are pertinent to distinguish. Fabrice here gives a rather common Italian answer: mandritto, roverso, fendente, stoccata, imbrocatta (although Sainct-Didier gives a French version of these names). The only other biographical detail, if it is to be taken as such, is this:

And then Fabrice answered and said, with several bottes, bottes in Neapolitan is the same as coups in French.

Quite a difficult quote to translate, because it just discusses two words in Italian and French that I’d translate “strike” or “blow” in English. Anyway, this would indicate an Italian and perhaps Neapolitan origin.

So what do we have here? We know that two Italians, perhaps Neapolitans, whose names are Fabrice and Jules, discussed fencing with Sainct-Didier a bit before 1573. The communication between France and Italy at that time is well documented. The mother of the King was Italian; it was basically expected of nobles to travel to Italy and learn fencing there; Italian fencers and fencing masters were quite sought after, and Sainct-Didier of course also went to Italy during his military service.

However, Fabrice and Jule are first names. Why would Sainct-Didier turn the last name Fabris into the first name Fabrice, instead of calling him Salvator, especially since he must have been still relatively unknown? What are the chances that among all these Italians around the court, the Fabris would be there to meet Sainct-Didier? Arsène Vigeant quickly jumps to the conclusion, maybe in an attempt to make Sainct-Didier, the first French fencing author, more relevant than he has been to the development of fencing, but all the indications in the text point rather to some other Italian than to the famous master. None of this formally disproves the meeting of the two masters, but it does mark it as extremely dubious.

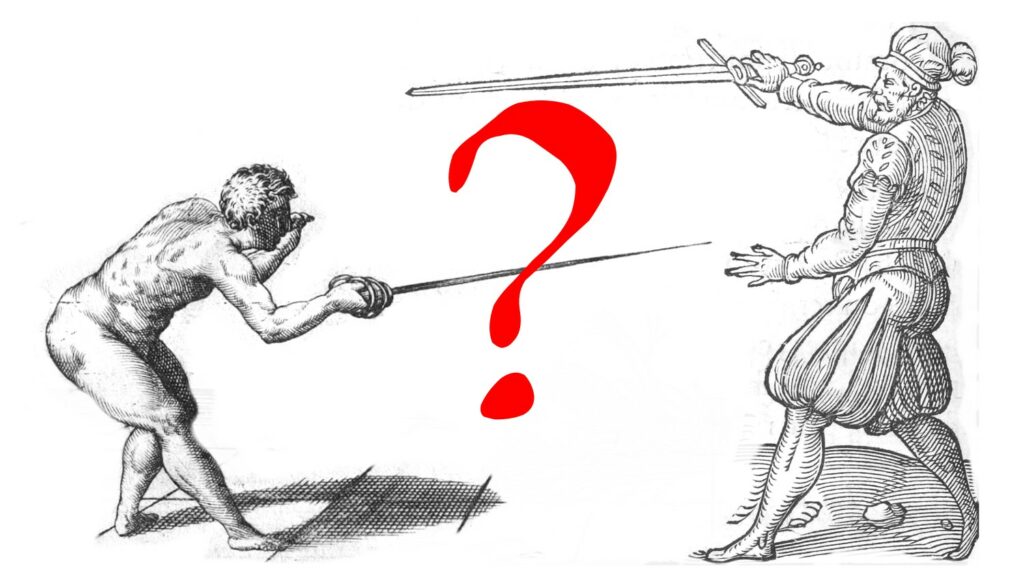

What is certain, though, is that there is very little commonality between the methods of Sainct-Didier and Fabris. They do not use the same classification of cuts, thrusts and guards, nor the same postures, they do not expose the art in the same way at all. Even if they had actually met at some point, there was absolutely no recognizable influence one way or the other. Their treatises are about as far appart as two rapier/sidesword works can be.