There is a common saying in martial arts that you should seek “the maximum efficiency with the minimum of effort”. It was made especially popular by its attribution to Judo founder Kanō Jigorō.

It is a good principle to keep in mind while polishing a technique. Ideally you want to discard all unnecessary motion and actions and keep only those that are strictly necessary for the effect you wish to obtain. The first benefit is of course that you are not expending as much energy, and the second one is that if you do expend more energy, it will all contribute to the desired effect, instead of being wasted.

It is however easy to err when applying this principle. All the problem lies in focusing too much on “minimum effort” at the cost of the effects themselves.

Efficiency can be defined as the ratio between the energy expanded doing something and the energy actually having the desired effect. For example, in an electrical motor, the input energy is in electrical form and the output energy is mechanical, the energy of the moving piece. In all systems that transfer energy, there is some form of loss, most often due to some kind of friction. The human body is no exception, of course. There is no mechanical system achieving 100% efficiency.

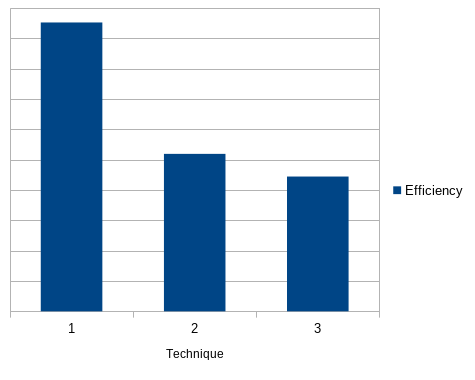

Let’s say we have 3 techniques which have their efficiency like this (the example is fictional, therefore the exact number does not matter):

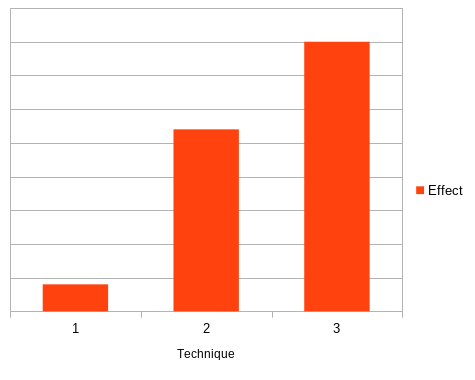

Pretty easy to see that technique 1 is the best, right? Maximum efficiency. The problem becomes apparent when plotting the actual effects of each:

So technique 1 is the most efficient, but also causes very little actual effect. Techniques 2 and 3 are better: they have more effects. Technique 3 has more effect than any other, and so perhaps this is what you want to pick?

Well, it depends. Maybe the last two techniques achieve some threshold of effect that is sufficient. Maybe technique 2 is better then, as it is more efficient than the other while still effective enough to do the job, and will therefore do so using less effort overall. Martial arts are full of questions like this. There are always compromises where you do not actually aim for the most effect, but cannot be satisfied with the less powerful techniques either.

The reader might think that my example is contrived. It actually isn’t; generally the effects of friction are going to be more important the more body parts you move, and the faster you go. Techniques that involve a lot of the body and achieve a lot of speed will generally be less efficient energetically, and of course martial arts gravitate around these.

To take a concrete example, a keystroke is an extremely efficient motion, and you can make a hundred of these in under a minute without even increasing your heartbeat. You cannot do that with a sword cut. But being hit by a hundred keystrokes certainly sounds better than being on the receiving end of even one sword cut.

When optimizing your techniques, always be mindful not to let their effects be diminished. This is a path that leads to picking an efficient but powerless technique. Use the minimum effort to achieve a given effect. You don’t want to pick the technique that feels effortless but is also effectless.

The next stage is to increase the effort, and see if you increase the effects. All techniques have a limit in terms of the energy you can channel through them; techniques that allow you to channel exactly as much as you want are going to be better. This is also one of the differences between a keystroke and a sword cut: you can do a sword cut that hits as lightly as a keystroke, but you cannot increase the power of your fingertip strike to the level of a sword cut.

One other pitfall that is especially pertinent to HEMA is that techniques can have a lot of potential but appear inefficient at the start, because they need a minimum of training to open the way to efficiency, or need a threshold of physicality to be possible at all. In a living art your teacher will guide you through this and show the technique with the most potential, but without this help it is easy to take the path of least effort that unfortunately leads nowhere. I have personally experienced that need; I had “optimized” a kenjutsu cut to be less tiring, and would have been locked for a while in a relatively ineffectual form if my teacher had not come and corrected it.

Navigating these compromises and complexities is of course part of the fun in martial arts!