Please see the introduction of this series for more information on the authors and context.

In his Discours sur les Duels, Pierre de Bourdeilles describes a duel between two Spaniards. Originally I intended to translate his account, but then I realized that he quite literally lifted it from another work called Le Loyal Serviteur (the loyal servant), a biography of Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard, a famous French knight who ended up being widely known as the good knight without fear and beyond reproach.

As I have pointed out above, this is a duel between two Spaniards. Also, it took place in Italy, and happened in the early sixteenth century, so before the duelling craze in France. One could argue it is misplaced in this series; it is only tangentially related to French people. However, I wanted to include it because it is interesting in several aspects, sort of bridging the gap between the formal knightly judicial duel and the later unofficial duels of honour. It also shows how familiar all the European people were with one another and how fluidly culture and habits were flowing around.

The context

Original (modernized)Le jour même que ce gentil duc de Nemours arriva à Ferrare, le baron de Béarn lui dit que s’il voulait, aurait le passe-temps de voir un combat à outrance de deux espagnols, dont l’un s’appelait le capitaine Sainte-Croix – et avait été colonnel des gens de pied du pape – et l’autre se nommait le seigneur Azevedo – qui avait aussi eu quelque charge desdits gens de pied. L’occasion de leur combat était que ledit Azevedo disait que le capitaine Sainte-Croix l’avait voulu faire tuer méchamment et en trahison et qu’il l’en combattrait. L’autre répondait qu’il avait menti et qu’il s’en défendrait ; par quoi était venu ledit Azevedo à Ferrare pour se présenter au duc de Nemours afin de lui faire donner le camp. Ce qu’il fit après que ledit baron de Béarn le lui eut donné à connaître. Ainsi Azevedo, bien aise d’être assuré du camp, le manda incontinent à son ennemi Sainte-Croix, qui ne fit pas longue demeure. En attendant sa venue fut dressé le camp devant le palais. Et deux jours après que fut arrivé, Sainte-Croix – lequel vint bien accompagné, car il avait bien cent chevaux de compagnie, dont le principal et qu’il avait pris pour son parrain était domp Pedro de Coignes, chevalier de Rhodes et prieur de Messine, domp François de Beaumont qui peu auparavant avait laissé le service du roi de France et autre – délibéra parfaire ses armes. Et entrèrent en camp une journée de mardi, environ une heure après midi.On the very same day that this noble duke of Nemours arrived in Ferrara, the baron of Béarn told him that if he so desired, he would have the leisure to watch a fight to the death between two Spaniards, one called the captain Sainte-Croix – who had been the colonel of foot soldiers of the pope – and the other lord Azevedo – who also had some charge of these foot soldiers. The reason for their duel was that Azevedo maintained that Sainte-Croix had wanted to have him killed maliciously, by treason, and so wanted to fight him. The other answered that he had lied and that he would defend himself; and as a consequence Azevedo came to Ferrara to introduce himself to the duke of Nemours in order to obtain from him the permission to duel. Which he did, after the aforesaid baron of Béarn had introduced him. Thus Azevedo, very happy to have the duel granted, immediately sent a message to his ennemy Sainte-Croix, who did not make him linger too much. While waiting for him, the fighting field was arranged before the palace. And two days after his arrival, Sainte-Croix – who came in good company, with at least one hundred horsemen, among which the chiefest was dom Pedro de Coignes, knight of Rhodes and prior of Messine, which he had taken for his godfather, also dom François de Beaumont, who had left the service of the king of France just before, and others – decided to settle the matter. And so they entered the field on a Tuesday, an hour after noon.

The text here begins without much summary of what is happening as the reader is supposed to be well familiar with what were basically current events at the time. The duel takes place during the War of the League of Cambrai, which is the third stage of the Italian Wars. The war takes place in Italy, but involved pretty much every significant power in Western Europe.

The basic political situation here is that the duke of Ferrara, Alfonso I d’Este, was an allied of the French, and that the duke of Nemours, Gaston of Foix, was there to command French troops and help him against the Veneto-Papal alliance. The Spanish crown was successively allied and enemy of the French. According to the chapter just before this one, this event took place right after Bologna was taken by the French, which was on May 23, 1511. At that point, the Spanish were enemies of the French and of the duke of Ferrara, but manifestly it was not a problem for duelling matters!

The form of the duel is very similar to the judicial duels. Assisting the fighters, you have godfathers, who take no part in the actual fight, and not the later witnesses. The fight happens in public in a specific place that is prepared for the occasion, under the eye of a higher authority – the duke of Ferrara. The motive of the duel is in a form that will become classical in the following century: someone makes an accusation, the other is calling him a liar, a fight is arranged. It is not clear in that instance that any judicial authority was involved on the matter, and apparently no conciliation was sought.

The preparations

Original (modernized)Premier entra l’assaillant, qui était Azevedo, avec le seigneur Federic de Bazolo de la maison de Gonzague, qu’il avait pris pour son parrain, et si ne savait pas encore comment son ennemi ni en quelles armes il voulait combattre. Toutefois, comme bien conseillé, s’était garni de tout ce qu’il lui était nécessaire, en homme d’armes, à la genête et à pied, en toutes les sortes qu’il pouvait imaginer qu’on sut combattre. Peu après qu’il fut entré va devers lui le prieur de Messine qui fait porter deux secrètes, deux rapières bien tranchantes et deux poignards, lesquels il présenta au seigneur Azevedo pour choisir. Il prit ce qu’il lui était besoin. Et ce fait se mit Sainte-Croix dedans le camp. Tous deux se jetèrent à genoux pour faire leurs oraisons à Dieu. Après, furent tâtés par les parrains, savoir s’ils avaient nulles armes sous leurs vêtements. Ce chacun vida le camp qu’il n’y demeura fors les deux combattants, leurs parrains et le bon chevalier sans peur et sans reproche qui par le duc de Ferrare et pour plus l’honorer – aussi qu’il n’y avait nul homme au monde qui mieux s’entendit en telles choses – fut ordonné maître et garde du camp. Le héraut commença à faire son cri tel qu’on a acoutummé faire en tel cas : que nul ne fit signe, crachat ne toussat ni autres choses dont nul desdits combattants put être avisé. Ce fait, marchèrent l’un contre l’autre.First to enter was the offender, who was Azevedo, with the lord Federic de Bazolo from the house of Gonzaga, who he had picked as his godfather, and he did not yet know how and with which weapons his ennemy wished to fight. However, having received good advice, he had come with everything necessary to fight as a military man, a la jineta and on foot, in all the modes that he could imagine it was possible to fight. Not long after he had entered, the prior of Messine came before him, and he was having carried two secretes, two keen-edged rapiers and two daggers, that he presented to lord Azevedo so that he could choose. He took what he needed, and on that Sainte-Croix entered the field. Both of them fell on their knees and prayed to God. After that they were searched by the godfathers to make sure they had no armor under their cloths. Then everybody left the area of combat, except both fighters, their godfathers and the good knight without fear and beyond reproach, who had been appointed as master and warden of the field by the duke of Ferrara, to honour him, and as well because there was no man in the world with better knowledge of these things. The herald started to shout as is customary in such cases: that nobody did any sign, spit or cough or whatever could be of help to either fighter. That done, they walked against one another.

Here again the process is fairly traditional. Leaving the choice of weapon to the offended party was a fixture of duelling right up to its last days in the 20th century. There were often arguments about it, especially in the early period. Indeed it was a known trick for the offended to ask the offender to bring all manner of weapons just in case, which can of course be costly and take time to assemble, and delay the actual choice to just before the duel. Pierre de Bourdeille claims that this is exactly what happened in the Jarnac-La Chataigneraie fight. There were also often discussions about the nature of the weapons themselves: one basic tenet of duelling usage was that only weapons commonly used by men at arms could be elected, primarily in order to exclude exotic weapons which a fighter could pick because he was familiar with them, and not his foe.

But here there was apparently no argument on either side. However there are several specific details to observe:

- This is among the first occurrences of the word “rapière” in French. Pierre de Bourdeilles claims that he is using it “to better respect the antiquity of the text”, marking that to him, at the end of 16th century, it was an outdated word. What kind of swords these were is entirely up for discussion. The only thing known for sure is that they have a serviceable edge. There is, as far as I know, no hard evidence on what exact type of sword would be called rapier at that time. A type XIX would certainly match, though.

- This is one early example of a duel to be fought with sword and dagger. I have had trouble so far finding references earlier than that. Sword and shield seems to have been more common, but sword and dagger gradually displaced that combination until it became the pairing of choice at the end of the 16th. As we will see later during the fight, it is not obvious that both fighters were familiar with that mode of fighting.

- Almost no armour is worn. The only piece is a basic helmet called a secrete, which protects neither the face nor the neck. Interestingly, it pops up in some of Fabris’ illustrations almost a century later

Quite clearly this was not exactly what Azevedo expected, but he made no difficulty. That equipment ends up being very similar to that of the later unofficial duellists.

The fight

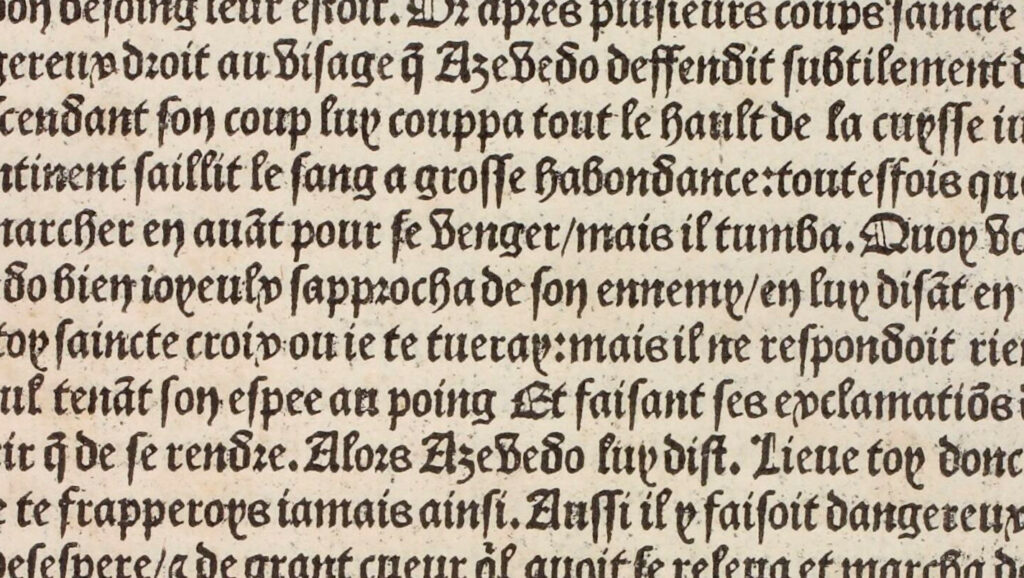

Original (modernized)Azevedo en la main droite mit sa rapière et en l’autre son poignard, mais Sainte-Croix mit son poignard au fourreau et tint seulement sa rapière. Or vous pouvez penser que le combat était bien mortel, car ils n’avaient nulles armes sur eux pour les couvrir. Sagement se jetèrent plusieurs coups et avaient chacun bon pied et bon oeil. Et bon besoin leur était ! Or après plusieurs coups, Sainte-Croix en rua un dangereux droit au visage, qu’Azevedo défendit subtilement de sa rapière, et en descendant son coup lui coupa tout le haut de la cuisse jusqu’à l’os, dont incontinent saillit le sang à grosse abondance. Toutefois que Sainte-Croix cuida marcher en avant pour se venger, mais il tomba. Quoi voyant par icelui Azevedo, bien joyeux, s’approcha de son ennemi en lui disant en son langage : “Rends-toi, Sainte-Croix, ou je te tuerai”. Mais il ne répondait rien, ains se mit sur le cul tenant son épée au poing. Et faisant ses exclamations, délibère plutôt mourir que de se rendre. Alors Azevedo lui dit: “Lève-toi donc, Sainte-Croix, je ne te frapperai jamais ainsi”. Aussi il y faisait dangereux, comme à un homme désespéré. Et de grand coeur qu’il avait, se releva et marcha deux pas en avant, cuidant enferrer son homme, qui recula un pas rabattant son coup. Si tomba pour la seconde fois Sainte-Croix, quasi le visage contre terre, et eut Azevedo l’épée levée pour lui couper la tête. Ce qu’il eut bien fait, s’il l’eut voulu, mais il retira son coup. Et pour tout cela, ne se voulait point rendre Sainte-Croix.Azevedo put his rapier in his right hand and his dagger in the other, but Sainte-Croix kept his dagger in the sheath and held only his rapier. You can see that the fight was mortal, since they had no armor on to protect themselves. Wisely they threw several blows, and both had good eye and good footing. And they certainly needed that! After several blows, Sainte-Croix threw a dangerous one straight to the face, that Azevedo subtly defended with his rapier, and descending his blow opened the top of the thigh right to the bone, and from it immediately sprung a great abundance of blood. Sainte-Croix wanted to step forward to avenge himself, but he fell. Seeing this, Azevedo with much happiness got near his ennemy and told him in his language: “Surrender, Sainte-Croix, or I will kill you”. But he did not answer, and instead sat on his butt holding his sword in his fist, started to shout and thinks rather to die than surrender. Then Azevedo said: “Rise up Sainte-Croix, I will never strike you like that”. And it was dangerous too, facing a desperate man. With much courage, he rose up and made two steps, seeking to skewer his man, who just stepped back beating down his blow. And thus Sainte-Croix fell for the second time, his face almost to the ground, and Azevedo had his sword lifted to cut his head. Which he might have done, had he wanted to, but he held back his blow. And in spite of all of this, Sainte-Croix did not want to surrender.

The first surprise is the choice from Sainte-Croix of not using the dagger from the onset. All the more so since he was the one who picked that weapon combination! It is possible, but this is only a guess, that in his mind the dagger would have been used only when the fight had come to grips and wrestling, and that he did not expect Avezedo to use both weapons at the same time.

In any case, the daggers did not end up playing a big role. The decisive blow is described as a parry followed by a cut to the thigh. A possible interpretation would be a parry from the outside to the inside which then forcefully binds down in the other direction, cutting the thigh in the process. This is something that can be done with single sword just as well.

The consequences of that wound to the leg are interesting. It certainly was not immediately lethal, but it did prevent Sainte-Croix from avenging himself. Notice how good of an illustration it is to the Bolognese contrapasso, a concept better known in HEMA circles as the afterblow, discussed in these terms in the Anonimo Bolognese (trans. Stephen Fratus):

[…] very often it happens that one will have been hit and will desire to go after the enemy to get his vengeance, but the blow is of such nature that it is not possible for him to move, for he may have been knocked to the ground. In respect of this fact, in the art of play one may not pass forward more than one step after having been hit, because although you may wish to take more steps forward, I say that if the swords were sharp, the attack may be of such nature that you may not be able to rush forward, for the blow may have laid you low.

It was a rule in their play that after being hit, you could retaliate as long as you did so within a single step. The reason given is that with sharp swords you might not be able to do more; the outcome here is a perfect example of that. Sainte-Croix did not fall on the spot, but could not step as much as he’d have liked either. Also note how prudent Azevedo remains after that first wound. At this point, he is just waiting for the opponent to get weaker and weaker, and he was not so hell bent on finishing him off either, certainly not before he was in such a position that there were no more risks.

Leg wounds are not so common in duelling accounts. Then again, often we do not have such a precise description of the hits. The duel between Jarnac and La Châtaigneraie is a famous example. Pierre de Bourdeille gives another one, where the leg wound did not stop the fighter who ended up winning anyway.

The epilogue

Original (modernized)La duchesse de Ferrare, avec laquelle était le gentil duc de Nemours, le priait à jointes mains qu’il les fit départir. Il répondait “madame, je le voudrais bien, pour l’amour de vous ; mais honnêtement je ne puis ni ne dois prier le vainqueur contre la raison”. Sainte-Croix perdait tout son sang, et si plus guère y fut demeuré, mort était sans remède. Par quoi le prieur de Messine qui était son parrain s’en vint à Azevedo auquel il dit : “Seigneur Azevedo, je connais bien au coeur du capitaine Sainte-Croix qu’il mourrait plutôt que se rende. Mais voyant qu’il n’y a point de moyen en son fait, je me rends pour lui”. Ainsi demeura victorieux. Si se mit à deux genoux et fort humblement remercia notre Seigneur. Incontinent vint un chirurgien qui étancha la plaie de Sainte-Croix. Et ses gens le prirent entre leurs bras et l’emportèrent hors du camp avec ses armes, lesquelles Azevedo envoya demander, mais on ne les voulait rendre. Si s’en vint plaindre au duc de Ferrare, qui le dit au bon chevalier, lequel eut la commission d’aller dire à Sainte-Croix que s’il ne voulait rendre les armes comme vaincu, que le duc le ferait rapporter dedans le camp où lui serait sa plaie décousue, et le mettrait-on en la sorte que son ennemi l’avait laissé quand son parrain s’était rendu pour lui. Quand il vit que force lui était, rendit ses armes au bon chevalier, qui comme le droit le donnait les bailla au seigneur Azevedo. Lequel avec trompettes et clairons fut mené au logis du seigneur Duc de Nemours. On lui fit beaucoup d’honneur, mais depuis il en récompensa mal les français, qui lui fut grosse lâcheté.The duchess of Ferrara, with whom was the noble duke of Nemours, was praying him to separate them. He answered “Milady, I would like to do so, for the love of you ; but honestly I neither can nor must ask the victor against reason”. Sainte-Croix was losing all of his blood, and if he had remained there much longer, he would have died without a doubt. For this reason the prior of Messine, who was his godfather, came to Azevedo and told him: “Lord Azevedo, I know well that the heart of captain Sainte-Croix would rather have him die than surrender. But seeing that there is no way he will do it, I surrender for him”. And thus [Azevedo] was victorious. On the spot he knelt down and very humbly thanked our Lord. Immediately a surgeon came who dressed Sainte-Croix’ wound. And his people took him in their arms and carried him out of the field with his weapons, which Azevedo later demanded, but that request was refused. He complained about that to the duke of Ferrara, who passed it to the good knight, who was sent with the message to Sainte-Croix that if he did not surrender his weapons as he was defeated, the duke would have him carried back into the fighting area, where his wound would be unsewn, and he laid down just as he was left by his ennemy when his godfather surrendered for him. When he saw that he was forced to do so, he left his weapons to the good knight, who rightfully gave them to lord Azevedo, who was then led to the house of the duke of Nemours to the sound of trumpets and bugles. He was much honoured, but since then he poorly rewarded the French for this, and that was very cowardly of him.

The duchess of Ferrara referred to here is the famous Lucrezia Borgia.

It was quite exceptional for a godfather to surrender in the name of the fighter. Normally, only the master of the field could break up the fight, and here it seems he was not so keen to do so. Pierre de Bourdeilles mentions conflicting customs on that point. The older custom was to let the fighters sort it out, with the only possible outcome being death or one of them surrendering to the other. But there were also a lot of examples of masters of the field (most often the highest authority in town) sparing the lives of the fighters when they felt that honour was satisfied. This was actually one of the argument in favour of official duelling: neutral authorities watching the fight could limit the loss of blood and life.

The drawback was obviously that some fighters could claim that they never had surrendered, just as Sainte-Croix tried to do here, despite the fact that it had been plain obvious to the whole assistance that he had lost. The duke of Nemours certainly found a vivid visual way of reminding him of that!

As pointed out in the introduction there is actually only a minor link between France and this duel. Note however that national boundaries seem to have mattered a lot less to them than we might expect. All the participants and spectators here consider themselves as nobles first, French, Italian or Spanish second, and as such there was no search for strict national limitations. Seeking a foreign ruler to grant you a permission to duel even became relatively commonplace later! They are all operating under the same assumptions and social habits, and only in the very details of the conditions would it be possible to identify national habits.

The wars in Italy were the occasion for the French to further mingle their culture with the Italians. That lasting influence was later blamed for the duelling craze in France. But here we see that even in Italy not everything was purely Italian; it seems that the Spanish could also be seen as originators of some of the aspects: no armour, primarily on foot, with particular swords which warranted the adjective “rapière”. It is hard to assess exactly how representative of Spanish habits this duel was, but being included in the biography of one of the most popular French knight ever almost certainly gave visibility and legitimacy to this mode of combat.

I think the best English translation for “à la genête”, which I noticed you put into Spanish in your translation, would be “on jennet-back”, a jennet being a small, Spanish horse breed. I understand the suggestion or implication of that sentence to be of three degrees of equipment: fighting as an man-at-arms, i.e. on a heavy horse and in full armor, on jennet-back, equipped as a light cavalryman, or on foot, the most lightly outfitted.

That’s a very good remark, thanks!

I have picked the Spanish form a la jineta in imitation of Jeffrey Forgeng’s Monte translation.

You might be right about there being degrees of equipment. However I’m not sure on foot would always be the lightest form; after all you could also be armoured on foot, more than these two were at any rate.

Well, I’m pretty sure you’ve read all the same accounts I have, only more of them and in the original languages, so I by no means mean to set myself up as an expert here. For what little it’s worth, though, my impression from reading Brantôme and others is that in this late period of officially sanctioned duels before the French kings stopped granting them, the common procedure was to start on horseback if you intended to fight in armor, then dismount after some given limit of mounted exchanges — whether a number of passes, a number of broken lances, one participant being unhorsed, or any other such limit. (I actually can’t off the top of my head recall reading a single instance of a duel being settled while the participants were still mounted, so that it seems almost like a formality.) Thus if what you really wanted was to go at each other with pollaxes or the like, you would shift to those once dismounted. So that’s where I get that idea of degrees.

That said, of course I’ve also seen the accounts of various, and occasionally extreme, sophistries concerning the equipment, but those seem to be condemned by all involved and not the expected behavior of valiant and honest men.

There was almost certainly a trope of knightly combat, going well back to the 12th century, starting on horseback then finishing on foot, and so you’re probably right that duellists would have wished to emulate this.

Worth noting though, that Brantôme describes a couple of early duels happening in armor and on foot, and not so many on horse. There is for example the one of Bayard vs. Sotomayor. So maybe there was some shift in trends at around that time? Hard to guess.