Please see the introduction of this series for general information about this project.

I regroup here all the information that can be pulled from the manuscript. Lovino was Milanese. His manuscript can be approximately dated from the dedication to Henri the third, king of France and Poland. Technically, this double role of Henri the third only lasted from February 1575 to December of that same year. However, the king still used the title of king of Poland up to his death in 1589. Another open question is whether the manuscript was created some time before the final dedication; that sort of illuminated and finely calligraphed book is not some overnight work!

The author claims a significant experience of 22 years in the text itself. Broadly speaking, we can consider that we are looking at fencing happening in the decades 1560-1590.

Morphology

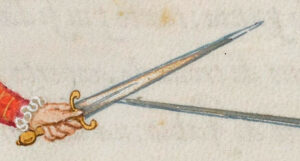

The blade of the sword shown is rather narrow. It is the case of all the swords in the manuscript, even on two-handed swords. The blade width can be estimated at slightly more than a finger.

The sword’s hilt is simplistic on most illustrations. The quillons are straight, with two finger rings. The way to hold the sword is precisely described and illustrated, and places the thumb on the ricasso, opposing the index, and that is the minimal hilt form for this. However, it is very possible that this simplicity is an artifact of the illustrations, and might be down to a wish to clarify the hand positions; indeed the guard is shown with a knucklebow on the first plate, and with a looping branch outside the hand on the second. The exact representation of a complex hilt is difficult in drawing, especially with varied perspective.

In 1580, the rapier hilt has reached its full development as far as the branch structure is concerned; all kind of hilts are therefore historically plausible at that time in France and Italy. Limiting ourselves to guards with two quillons, optionally an outside loop and a knucklebow, and which are attested in 1560-90, it is possible to restrict ourselves to the following Norman types:

- Guards with projecting lug(s) perpendicular to the plane of the blade, starting from the end of finger-rings

- two lugs, a lateral ring on the quillions (22)

- same, with a knucklebow (23)

- same as 22, but the quillon ring merges into the end of the rear finger-ring (26)

- one lug on the front finger-ring, a branch joining the other to the forward quillon, no knucklebow (28)

- same, with a knucklebow (30)

- Guards with a side-ring on the end of the finger ring (39)

- with a knucklebow (41)

- with a side ring on the quillons (43)

- with a side ring on the quillons and a knucklebow (46)

- with a knucklebow, a loop-guard joining the rear finger-ring with the knucklebow (53)

- with a diagonal guard joining the rear finger-ring to the root of the front quillon (69)

- same, with a knucklebow (72)

The dagger is of an unusual type in fencing books. The blade is wide at the base and tapers almost triangularly to the tip. The quillons are short and curved towards the blade, sometimes to the degree of touching it. On plate XXXII, a possible side-ring on the quillons at the base of the blade might be represented.

This form is quite different from that of the parrying daggers that are often found associated to rapiers, which rather sport a narrow blade and long quillons that stray far from the blade. The dagger here almost evokes the cinquedea without reaching such an extreme. A median line can be made out in some of the plates, which might be showing either the ridge of a diamond cross-section, or a narrow fuller on the upper third of the blade.

The weapons are manifestly matched although their depictions are not very detailed. It was somewhat common to create pairs of sword and dagger with a shared construction and decoration, destined to be worn together. Here, in particular on plate I which was shown above, the pommels are depicted as bulbous, circular in section perpendicular to the blade, and with grooving and fluting materialized by radial touches of paint. The pommels are oval or round in the plates, never flattened in the blade’s direction. In Norman’s typology, the only type of pommel attested in this period with these characteristics is type 15.

Dimensions

The dimensions of weapons are hard to estimate. The proportions of the characters seem modified, maybe to ensure a better use of the page’s space: the legs are proportionally longer compared to the arms. On figures that are alone on the page, the blade could have been voluntarily shortened; for example on plate II, the blade is barely as long as the arm, and the cross wouldn’t even reach the crotch if the sword was vertical, tip on the ground. But it is easy to think that the blade was drawn that short in order to neither overflow from the page nor reduce the character. Functionally, the plates that show an interaction, for example a wound with opposition (plates IX and X), or that place both weapons in relation in a guard position (plate XXXII), are probably more truthful as to how long the blade should be.

Conveniently, the blade length that I could estimate for me in these situations is roughly one meter.

The size of the dagger’s blade is also difficult to precisely establish. The illustrations vary between short blades (2:1 ratio between the blade and the hilt) and long ones (3:1 ratio), with long ones being more common.

Functional constraints are harder to come up with for the dagger blade length. Perhaps the most interesting plate in this regard is number XXXVI, which shows a simultaneous attack of sword and dagger.

On the face of it, this gives rather long dagger blades. Assuming a 100cm sword blade, the dagger blade goes easily into the 40cm and 4cm width at the base. This trend is consistent in the other images where that type of inference can be made (plates XXXIII and XXXVII). As will be shown in another part of this series, this is however not consistent with the daggers commonly found in period. It is possible that the illustrations are exaggerated in some regards; perhaps the illustrator wanted to really make the daggers stand out on the plates and therefore made them longer and bigger. It is striking that all the weapons in the manuscript including two-handed swords have the thin look, the only exception being the daggers. Perhaps this was purposefully done to make them stand out more, and not as some realistic representation.

Use

The fencing style described by Lovino makes a balanced use of all the offensive and defensive capabilities of the weapons, and particularly uses cuts and thrusts without any particular preference of one over the other. The sword is used for fast beats, feints, forceful displacements of the opposing blade. Several plates show wrestling at the sword, including pommel and hilt strikes. The dagger is used defensively but also to wound with the point; in fact such an action appears in all the plates about sword and dagger that show a wound at all. This is probably down to a will to focus on a specificity of that weapon combination, given that the previous chapters on sword alone already gave a lot of details about the sword can be used. However, this is relatively original, especially compared to later works on rapier and dagger.

Still, the overall feel is that the sword has to be quite agile. There seems to be a sort of transition to later forms of rapier fencing at play here. There is an emphasis on finding the sword. There are threats to the hand, fast evasions, extended guard positions that could be hard to perform with heavier, cut-oriented swords.

In the next article in this series, we will get away from the manuscript and look at contemporary paintings for inspiration.