Please see the introduction of this series for general information about this project.

Given the information in the manuscript, we are looking for:

- a matched pair of sword & dagger

- the sword, with a narrow blade and relatively simple hilt

- the dagger with short curved quillons and a triangular blade

- the whole of Milanese origin, or at any rate Italian, with a golden décor, and datable in the second half of the 16th century

Swords

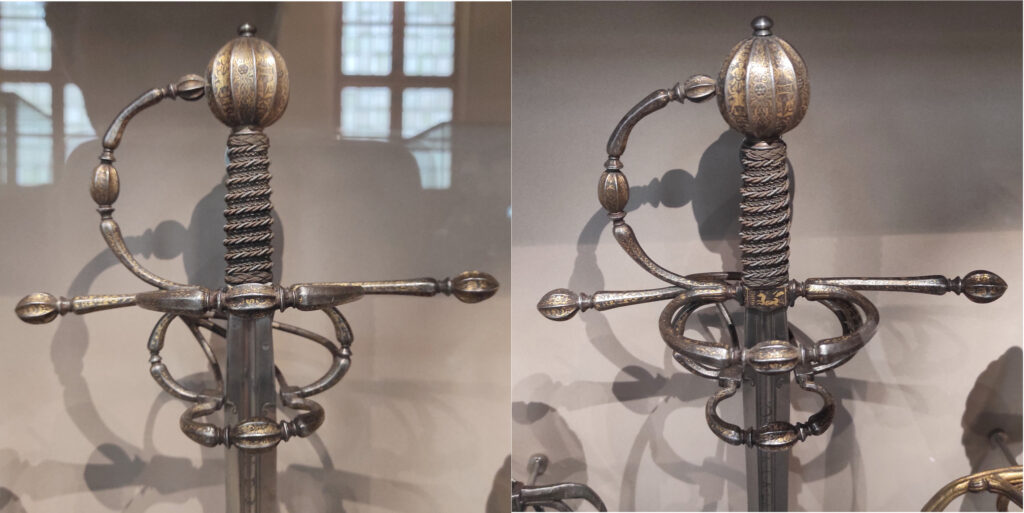

The Rüstkammer in Dresden holds several pairs and swords which are close to this goal. All are noted as Milanese works from around 1560 and are not really suspect of being composite pieces. There is a pair of swords which are a very good match from the point of view of hilt and blade type, with a décor based on hollowed-out elements: numbers VI 0112.01 and VI 0241. On these swords, we have rather narrow blades, which combined to the simple and carved guard elements give very light weapons, of less than a kilogram. The golden décor is damascened on darker steel (the most common technique is “false damascening”, in which the gold leaf adheres on hatched parts of the steel below). That type of décor can be found on other weapons of the same period and origin, for example IV 0082, and Wallace Collection A572.

In a similar vein, there is example 3757I of the French Musée de l’Armée, although this one is identified as French provenance.

There is a group starting to emerge here : weapons with hilt type 39, blades on the narrow side, about one meter long, guards decorated via damascening, with a systematic callback between the pommel, the quillons extremity and the middle of the side-ring. The quillons often have a slight curvature in the plane of the blade and the perpendicular as well. The handles are also all notably of “smooth” metal instead of the more common wire wrap. This specificity also appears on other examples from other origins or a later time (see The Sword – Form & Thought, ex. 44 and 46). This might raise the question of the functionality of this assembly, indeed it seems that the surety of the grip with a gloved or bare hand would be lessened.

In the same group, with a wire wrap, the J 106 of the Musée de l’Armée (the hilt is basically the twin of VI 0241, aside from the handle):

In Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, there is another pair with less complex sculpture, without the hollowed-out elements, and a different hilt type. Here again it seems that the décor was damascened on dark steel, maybe appearing darker than originally because of abrasion wear, which is the weak point of this decoration technique.

It is interesting to note the difference between the masses of VI 0112.01 and A794, which otherwise have practically the same dimensions. Assuming there was no mistake in measurements, it might be explained by the hollowed-out guard and hollow ground blade on VI 0112.01.

Still in Dresden’s Rüstkammer, another example of Milanese work of that time, which is a better fit from the point of view of the pommel and quillon style. The associated dagger is also quite close to the illustrations.

The big differences are the hilt complexity of the sword and its type of blade. It seems a bit too wide and heavy to really match Lovino’s style (in art and in fencing). The pommels, albeit fluted in a way that is consistent with the illustrations, might be a bit too flattened in the blade’s direction. The branches are thin but with subtle variations in thickness: they are wider towards the quillons’ end, and in the middle of the rings.

One weapon seems to stand halfway, with fluted pommel and thin branches, but also elements calling back to the pommel on the branches and quillons (J 126 in the Musée de l’Armée) :

Note that the pommel type here is in very good correspondance with the illustrations, as well as the type of décor and the dating. The branches of the guard are hexagonal in section. The blade is longer than in the other examples. The blades of both Musée de l’Armée swords are of similar type, although that of J 126 is longer than that of J 106: hexagonal cross-section, with a fuller on the ricasso and the first quarter or third of the blade. This differs from the first group which rather shows simple diamond cross-sections.

There is another kind of décor that is found on swords of that time period and origin (as well as portraits, as we have seen in the previous post): a sort of checkered pattern created via regular grooves in the guard and pommel. It appears here on Metropolitan Museum 04.3.287 and Museo Poldi Pezzoli 2575:

It is extremely difficult to gather information about blade width and thickness. The best information I have at my disposal is in the catalogue Le spade da lato al Museo Stibbert. These are less decorated weapons, which could let suppose that they were functional (whereas the very ornate guards of VI 0112.01 and VI 0241 could also bee seen as artistic tour de force, without regard for functionality) :

- 4764 (1): blade 104.5cm, ricasso 25mm x 7mm, mass 1195g (noted as Milanese origin)

- 3430 (2): blade 92.5cm, ricasso 20mm x 8mm, mass 915g

- 2543 (11): blade 91cm, ricasso 26mm x 6mm, mass 905g

- 2213 (12): blade 98.5cm, ricasso 27mm x 7mm, mass 1145g (same type of hilt as VI 0112.01, VI 0241)

- 3579 (14): blade 100.5cm, ricasso 28mm x 7mm, mass 1085g

We see that thicknesses tend to be around 7mm, for total weapon weight of around 1kg.

Daggers

As pointed out above, the Rüstkammer museum has several pairs of sword and dagger of Milanese provenance:

blade 21.3cm, 203g)

The daggers have very short straight quillons, no rings, and rather short blades that do not have the triangular profile shown in Lovino’s manuscript.

The dagger in the Kunsthistorisches Museum is perhaps the best match in terms of overall looks, but is much shorter than what the images show:

The dagger associated to the big wide sword in the Rüstkammer is also a possible candidate:

Most daggers of this type seem to rather have a blade terminating with a reinforced point and a rupture in the triangular profile of the blade, the angle becoming more obtuse towards the tip. However, I have seen in a recent temporary exhibition in the Musée de l’Armée a strongly triangular dagger which makes a better match. Sadly, it was displayed in a position that prevented close-up observation, and without any information of provenance or dating:

Overall truly triangular blades seem to be in the minority. Here is another one, but of a later date, in the Royal Armouries:

An interesting exercise is to relate the depicted swords and a museum example. It makes it even more apparent that on some plates the blade is very likely shortened, whereas other blades make a very good match (bearing in mind that perspective deforms the photographic shots, of course, so this is all quite approximative).

In final article in this series, I will detail the choices I have made and how the final sword and dagger turned out!