The topic of how exactly to grip your sword seems like an important one. Indeed, the grip is what transmits force from your body to the sword, and reciprocally. It is absolutely central to all actions! However, there is surprisingly little gripping advice in technical sources. There are three possible reasons for that:

- the grip position is intuitive to a degree, even more so in a culture or social milieu where fencing is a common activity

- it is the first thing taught to beginners, out of necessity. Since the readers seem to be assumed to already have experience in fencing by most sources, there is no real need to go over such a basic topic

- it is very difficult to express in words, especially when considered in motion rather than in static positions

In this article I would like to focus on the advice we have for the rapiers. For this purpose, I will define the rapier as any one-handed sword with the characteristic hilts, more complex and protective than a single cross. In particular they include arms of the hilt, curved branches rising from the quillons and protecting the ricasso, an unsharpened portion at the base of the blade. This form of hilt appears around the 1470s in Italy and Spain and lasts into the 18th century in certain regions (essentially Spain). In HEMA terms this lumps together rapiers and sideswords; it excludes smallswords (which often have arms of the hilt, but not big enough to usefully put fingers in them). As we will see, these hilts are particularly interesting because they allow for a number of fairly different gripping methods.

The ambition of this article is limited to source exploration. There are many considerations that could be developed with respects to how to grip, and many details that should probably be given to students, but here I wanted to just list what we can be certain of based on sources.

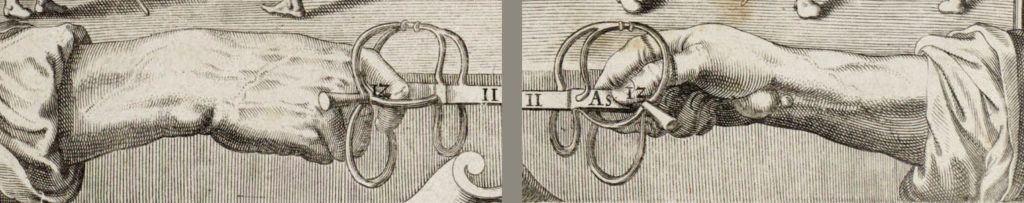

I will only go over sources with explicit textual advice. I have found illustrations to be fairly unreliable in this regard. The hilts of swords are often simplified. A gripping hand in a complex hilt is extremely delicate to draw well. Even in texts which have explicit and very prescriptive gripping advice, it is relatively easy to find spots where the illustrations are either messed up or contradictory, so I’d rather err on the side of caution and consider any illustration as doubtful in that regard. I will only include them here when they unambiguously support the text, which is not the most common case!

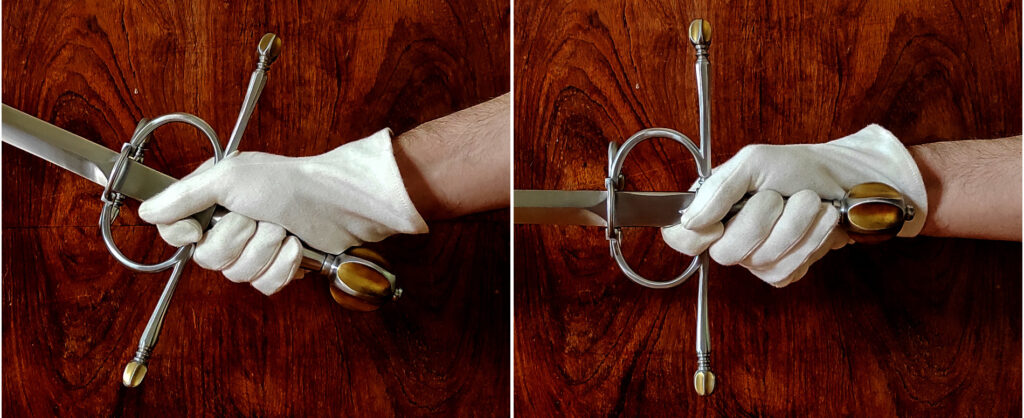

I have taken pictures to show how I interpret the grips described, when no illustration is present. These are of course interpretations from my part; in most cases the text could lend itself to several variations. Nothing set in stone! I have pictured all of the variants on the same sword (a wonderful example of Marco Danelli’s work, which I will write about in more details later), to make comparisons easier, and because this one has a very simple hilt structure that does not obscure the hand. However some grip variants are better suited to different swords, depending mainly on grip length and pommel shape, and I would definitely not recommend all of them for this particular sword.

The take-aways

I will start straight away with some of the conclusions that can be drawn, for the people who prefer to get straight to the point:

- There is no unanimous advice in the sources, no one single best method acknowledged universally

- In the era of swept hilts, the prescribed grips are never with more than the index over the cross (and in some cases at least, without)

- After the apparition of cup-hilts, we start to see advice to put both index and major over the cross, but it does not replace the previous gripping methods. It’s only one more alternative

- The thumb position and how it interacts with the other fingers and the blade is another important parameter that many writers insist on, still without universal agreement

- There is a widespread concern about the grip being solid enough to withstand heavy blows, an emphasis on not being disarmed, although some of the grips sacrifice this for reach

The sources

The early authors

The early sources are not actually that early compared to the dating of the first rapier hilts.

The first source I know of that discusses the grip is Viggiani (written 1551, published 1575). Sadly, he only discusses it to say that he will not describe it! As we will see, the difficulty of precisely describing how you grip a sword was very real, and many masters just avoid the topic entirely.

CON: Lovely! But how do you accomplish the settling of the sword in your hand after so much, and so many flourishes?

ROD: I cannot describe it to you, Conte, but open your eyes well, and pay diligent attention to my wrist, and foremost to the dexterity of the manner of resettling it. Do you see how I do it? Similar actions are to be demonstrated, and to be learned, more and better in proof, and with the sense of sight, than with words; and whoever wanted to express them in words would be in need of that which I know well– all the muscles of the hand, and the fingers; and I will tell you, that you need to do such and such motion, with this and that muscle, and relax the hand thus, and grip it thus; and he would serve in the role of a good doctor, and a professor of anatomy; because another would not understand it;

Meyer, in his 1570 book, in the section about the rappier (a thrusting sword which he describes as foreign), recommends a grip with the thumb on the flat of the blade (at least for the guard Pflug). However we are not really sure what sort of sword hilt he is considering; on the illustrations the hilt is complex but without arms of the hilt, so it might not allow for the full range of gripping methods that other rapier hilts do.

Pflug is in itself nothing else than a thrust coming from below, and it is also a guard. Do it thus: hold yourself with the right foot forward, as has been the case up to now, and hold your weapon with the quillons horizontal, in front and below your right knee. When holding your weapon, your thumb should be laid above the quillons, on the flat of the blade, and the other fingers must be turned away from you, downward and to the ground.

Lovino (ca. 1580) is the first master to unambiguously describe how to hold a rapier, to my knowledge. His treatise is particularly good in that regard, because his textual advice is very faithfully illustrated in the plates. The grip he recommends passes the index finger into the arm of the hilt, wraps the other fingers around the handle (particularly the last two, ideally so tight that they touch the palm), and finally puts the thumb on the back ridge of the ricasso.

I say the sword must be held firmly in the hand, such that the last two fingers touch the palm; and the second finger after the thumb goes over the cross of the hilt of the sword, holding the guard tightly; and then put the thumb on the shoulder of the sword. The sword held as such will be stronger in the hand and will not be easily forced from the hand of the one who holds it like so.

Ghisliero (1587) is the first to put up a list of ways to hold the sword. Four are given, not all are easy to interpret. The text itself is not very easy to translate; I have mixed two translations and my own. Only the fourth way is recommended. My interpretations of the four ways are:

- put the thumb on the back of the hilt (presumably the handle?). This favours cuts but opens the hand

- with the palm towards the ground, almost certainly with the edge plane horizontal, so that the sword rests against the whole palm. Of course this is a bit restrictive in terms of what hand position and angle you can reach

- in the fist so that you gain “a finger of reach”. I suppose this means with the hand closer to the pommel, which forces the sword to make an angle

- with the index over the cross

There are four ways to hold the sword.

The first is by placing the thumb on top of its hilt to facilitate a straighter cut. However, in this manner, thrusts are not executed effectively, and the hand does not exert its full strength due to being half-open.

In the second you can take it flat with the palm of the hand towards the ground. And this is done to have it seem lighter; since the hand with the arm in this state works almost as a support for the body, which makes the weight of the sword seem lighter; but in this way it will not cut and changes the lines in play, which is completely imperfect.

In the third way, the sword is taken in a clenched fist in order to gain a finger of reach. And this is true about the instrument [when considering only the sword relative to the hand]. But each time an attack is made, the instrument must form a straight line with the arm, as much as possible; this cannot be done with this grip, since in this way it always forms an obtuse angle, and besides most cuts will land flat.

The fourth and final way (and the perfect one) is to hold the sword with a closed fist and cross the index finger over the crossguard. This grip provides all the necessary advantages.

So here we see Lovino and Ghisliero broadly agreeing about the best grip, and this is the classical form taken by many people: index around the cross, closed fist. But there are nuances to that grip, and given his criticism of the first grip and his illustrations, I suspect that Ghisliero would not have used a thumb on the ricasso (as it opens the hand somewhat). And the enumeration of other grips is informative; it shows that even at that time, more than a few people were not crossing any finger above the cross, despite the fact that the hilt forms seem to have evolved around the need to do so.

The English debate

Funnily enough, this debate apparently was exported to England together with rapiers. Saviolo (1595) says to not put the index over the cross as this diminishes reach. His recommended grip seems somewhat close to Ghisliero’s first variant.

V. For your Rapier, holde it as you shall thinke most fit and commodious for you, but if I might advise you you should not holde it after this fashion, and especially with the second finger in the hylte, for holding it in that sorte, you cannot reach so farre either to strike direct or cross blowes, or to give a foyne or thrust, because your arme is not free and at liberty.

L. How then would you have me holde it?

V. I would have you put your thumbe on the hylte, and the next finger toward the edge of the Rapier, for so you shall reach further and strike more readily.

Silver (1599) indirectly gives gripping methods for the rapier, which he criticizes. He says the Italians love their more open rapier hilts because they can either put the index over the cross or hold by the pommel: this is a new one which we did not meet before!

Yet the Italian teachers will say, that an Englishman cannot thrust straight with a sword, because the hilt will not suffer him to put the forefinger upon the blade, nor to hold the pommel in the hand, whereby we are of necessity to hold fast the handle in the hand.

Swetnam (1617) describes grips in a way that is actually more consistent with Silver’s criticism, describing three methods and recommending to freely switch between them. The first uses the thumb on the blade, the second seems to be just a fist grip with the index locked by the thumb, the third is gripping by the pommel.

These are three waies for the holding of a Rapier, the one with the thumb forward or upon the Rapier blade, and that I call the naturall fashion, there is another way, and that is with the whole hand within the pummell of thy Rapier, and the thumbe locking in of the fore-finger, or else they must both ioyne at the least: this is a good holding at single Rapier.

Then the third is but to have onlie the fore-finger and thy thumbe within the pummell of thy Rapier, and thy other three fingers about thy pummell, and beare the button of thy pommel against the in-side of thy little finger; this is called the Stokata fashion, and these two last are the surest and strongest waies: after a little practice, thou maiest use all three in thy practice, and then repose thy selfe upon that which thou findest best, but at some times, and for some purpose all these kinds of holding thy Rapier may stead thee, for a man may performe some manner of slips and thrusts, with one of these three sortes of holding thy weapon; and thou canst not doe the same with neither of the other; as thus, thou maiest put in a thrust with more celeritie, holding him by the pommel, and reach further than thou canst doe, if thou holde him on either of the other tow fashions.

Againe, thou maiest turne in a slippe, or an overhand thrust, if thou put thy thumbe upon thy Rapier according as I have set it down, calling it the naturall fashion, and is the first of three waies for holding of thy Rapier; and this fashion will bee a great strength to thee, to give a wrist blowe, the which blow a man may strike with his Rapier, because it is of small force, and consumes little time, and neither of the other two fashions of holding will not perform neither of those three things; for if thou holde thy rapier either of the second waies, thou canst not turne in a slippe, nor an over-hand thrust, nor give a wrist blow so speedily, nor so strong: wherefore it is good to make a change of the holding of thy weapon for thine own benefit, as thou shalt see occasion: and likewise to make a change of thy guard, according as thou seest thy best advantage; I meane if thou be hardly matched, then betake thee unto thy surest guard, but if thou be matched with an unskillful man then with skill thou maiest defend thyself, although thou lie at randome.

Swetnam is the only author who recommends that pommel grip. However it is described and criticised by others, and so there must have been a number of people doing it. It is very similar to how a French-grip épée is held to reach further (this is called “posting” in modern fencing) but it is far easier with these lighter blades.

It is a bit unclear to me what the essential difference is between the first two gripping methods. Maybe it is just the thumb position. This would be further demonstrated in an other part of the text, where the author insists on this aspect.

and the thombe of thy rapier hand, not upon thy rapier, according unto the usual fashion of the vulgar sort, but upon the naile of thy fore-finger, which will locke thine hand the stronger about the handle of thy rapier,

It is possible also that the index finger would cross over in what he terms the “natural fashion”. However this makes it a bit harder to freely transition between all three methods.

The Iberian traditions

Spain and Portugal were also a place of birth for rapiers and the associated fencing traditions, although Italy was more successful with exporting its masters all over Europe for some reason. However, the Spanish empire included both the southern part of Italy and the Netherlands at some point, therefore we still find hints of Iberian influence in these parts. Iberian fencing is basically split between older school(s) and a new, more scientific approach pioneered by Carranza, which eventually came to be named la Verdadera Destreza (the true skill, LVD for short). All the other approaches ended up lumped under the name of “common fencing”, or in a more derogatory fashion “vulgar fencing”.

Narvaez (1600), a major LVD master, seems pretty fixated the problem of where the thumb should be, which is similar in principle to the last quote from Swetnam, albeit in a much longer text. He seems to be adamant that the thumb should lock over all four other fingers.

The ordinary and common use of taking the sword has been placing the finger that we call thumb (which is the first on the hand) above the recazo of the sword. This oversight has happened many times to knock it from the hand, by being in a bad posture as well as the manner of taking it, without dealing with the rest, as all is manifest with the one. The demonstration of the man demonstrates this well, which appears to have the sword in this way: the index finger, which is second on the hand, has gripped the quillons by the junction that its arms make, and the thumb above all four, closing and gripping the hand with all the virtue that the tendons, muscles, and sinews have. Placing the thumb above the other four is of no little consideration, as our author proves very elegantly that one only has as much strength as the other four. This being proven, seeing that when we want to make force with the hand, throwing or gripping anything, then we come with the thumb to favor the other four, because we feel them weaken easily. Also, when one makes a wager that they will not open the hand, it’s not with the thumb lifted, but with it gripping the others, as the key and lock of all of them. Finally, in every thing where one wants to make force with the hand, the thumb is what strengthens it, gathering the rest below themselves as support for all, as everyone will be able to consider in their own hand. Many times it has been seen in taking the sword as it is vulgarly taken, and in it being subjected, communicating some force, the four fingers alone not being able to resist it, nor having the sword and then coming with the thumb to favor them.

The sort of grip Narvaez criticizes here is pretty much that of Lovino. But putting the thumb over all four remaining fingers is a new indication. I found it difficult to grasp a rapier like this, to be honest. It is certainly strong but it is not conducive to extending the sword in the direction of the arm in my experience.

Godinho (1599) on the other hand is a vulgar master, and has a note concerning the grip. It is not particularly well-written or precise, and could be interpreted in two entirely contradictory ways!

Those that presume they will be diestros support greatly that the sword has to be gripped with the thumb on the third. I say that if, when the disciple has never taken the sword in hand, that it was created in that nature, but having already made a habit, in whatever other habit. I mean to say that the disciple does not have to be taken from the nature in which he is created, because natural ingenuity works much more than strength, where it is seen that in the pitched battles, the few defeat the many by having more natural ingenuity and accord. […] As follows, the strength that they praise is not true in the fight if it is not attached to the art more than strength.

He mentions people having an habit of “putting the thumb on the third”, but what “third” it is is unclear. The two possible interpretations are:

- the first third of the blade: then it would mean a grip much like Lovino’s

- the third finger of the hand: then it would rather be a grip like Narvaez’.

The author then develops an explanation of how strength is not the only consideration, so I am inclined to consider the second interpretation as correct and conclude that Godinho disagrees with people like Narvaez, which would be quite consistent with the opposition of styles.

Thibault (1628) publishes in the Netherlands and his treatise is manifestly heavily influenced by LVD ideas. However the grip he advocates is entirely original, and not described anywhere else. I have a whole article dedicated to it here. It might have been influenced by variants of the thumb grip like Meyer’s, but keeping the idea of looping the index into the arms of the hilt. It is an outlier among all the descriptions.

Viedma (1639) writes about the grip in an original way: instead of focusing on the fingers, he focuses on where the pommel should lie, pointing out that having it in the channel of the wrist lines up the blade with the arm, whereas having it below the blade of the hand keeps an angle.

There have been, and are, many masters that have wanted to maintain that the posture doesn’t have to be straight, saying that they appear to be more secure in that of the obtuse angle (iron gate) and the acute angle (the imagined), and that the sword is stronger, saying that the arm and sword have to be given curved. They live deceived, because that of the right angle is the best and has the greatest reach, but that of the obtuse angle is man’s own nature, which is placing the pommel of the sword below the blade of the hand. […]

This present demonstration clearly shows how the sword in the right angle reaches more than in the obtuse or the acute. The pommel has to be placed in the channel of the wrist, as has been said, and will serve to disillusion the vulgars that establish themselves curved […]. Although at the beginning it appears difficult, and one will say that he doesn’t have strength in the sword, use it, so that in a few days he will see its use, and the deceit in which he lived.

This is a very keen observation. Indeed the position of the pommel is a better descriptor of the angle between the hand and the handle than anything that can be described with the fingers. It must have been discussed more widely than that; the only other reference to the pommel position is in the manuscript Cod. Guelf. 264.23 (ca. 1657), from a fencing student who might have been down a teaching line tracing back to Fabris. It is precisely the opposite of Viedma’s.

You must hold the sword in the hand such that the pommel of the hilt lies under the thick flesh of the little finger. It shall also otherwise be held against the finger next to the thumb, and then the hand will be turned in Quarte half Tertie.

With Viedma and Thibault, we are reaching the end of the early rapier era. While shells and plates were being added since approximately 1590, the hilts were still primarily relying on a branching structure to protect the hand. Around 1630, new forms appear that change the construction method completely. One example of this is the cup-hilt, which became common in lands under Spanish influence.

The late rapiers

This brings us up to the next author, Pallavicini (1670), who is the earliest to introduce a grip with two fingers above the cross. He puts the thumb in opposition on the ricasso as Lovino does.

Fencing is founded in the sword alone, as the Queen of Arms, and it is not enough only to take it in hand, but to know to grip it well, not as some do that grip it with two fingers inside the incascio, others with one, others with none in the incascio. The better grip, however, is that which is done with two fingers inside the incascio and the thumb, as we say in Sicily, placed over the incascio. With much reason it must be gripped with two fingers in order to resist with more strength such things as the finding or rather the engagements of the sword, or also for those blows which some of little practice are in the habit of giving, to weaken the control over the sword, which if you do not hold it well, will without a doubt make it jump from the hand.

Although such a gripping method would have been perfectly possible with earlier hilts, it is notable that it only starts being described with the apparition of cup hilts, which happen to have shorter handles in some cases. It is also the grip that Rada (1705) argues for, although with a different thumb position, touching the middle finger.

There are three ways to take the sword in the hand: not inserting any finger inside the cup or guard, inserting only one, or inserting two. Inserting two is the safest way to work and maintain one’s defensive pyramids. Moreover, the sword will be grasped with more strength and can therefore be moved more swiftly. Consequently, one will be better able to resist an opponent’s attempts to place atajo; although, I will always advise you not engage in trials of strength, struggling with the other sword.

Therefore, our student will grasp the sword by sticking his middle (or big) finger and index finger inside the guard, pressed against the ricasso from below. They should be firm against the cross, with the ring and little fingers between the cross and pommel, squeezing the handle along with the thumb with such art that the thumb does not enter inside the guard but remains pressed alongside the cross. The tip of the thumb should be touching the tip of the middle finger. Do not grip the sword too tightly, squeezing the handle so much that it strains the arm. Moderate force is applied because, if the force is too intense or too relaxed, it will hinder the ease of the execution of the techniques.

The two fingers grip was seen as a Spanish specificity by Liancour (1686), in the part where he describes what to expect from a Spanish fencer and how to best deal with that.

All the more so since they [the Spanish] have a very bad way of gripping their sword, which is to pass two fingers in the form of a hook into their hilt, done on purpose with two rings, and the other three fingers on the handle, which gives them more freedom for their cutting blows.

That being said, even at that time there was no homogeneity. Marcelli (1686) says no to posting, no to two fingers over the cross. His recommandation is index over the cross and thumb locking it, much like Ghisliero a century before.

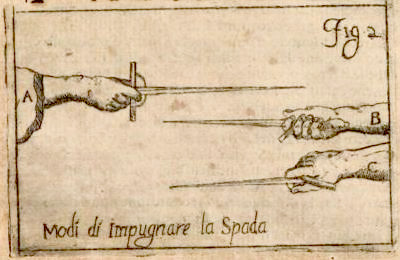

The present illustration shows the method of knowing how to grip the sword. Although I would have judged that developing a chapter of it would be of little importance, due to the hand being naturally guided to grip it; however, I have noticed the error of many, because I have seen others that grip it by holding only the pommel in hand, and almost whimsically, they play most weakly with the foil. Others to the contrary, not sufficing themselves to grip only the grip, grip it with two fingers inside the incascio. Both extremes are harmful, according to the judgement of Tacitus, “there is nothing moderate between extremes and rashness”. The first is weak, and is glimpsed daily in the Academies, where to every little shock or beat, the foil falls to the floor and the fencer stands without weapons (a truly considerable event, if it would have been produced with the sword, as it reduces him to an evident peril of not being able to defend himself; and for his salvation constrains him to give himself shamefully to flight). It is considered nothing by those, and they believe that this courtesy that comes to be used there by his competitor in the schools (stopping oneself in that action, in order to give time for him to recover the fallen weapon) is obligatory, and the opponent would even have to use it in a struggle, when that one does not have any obligation of doing it; but only, if he does it, there is no doubt that he makes a great, generous, and Christian act; but for this act to be done, with which his health is placed in doubt, and that his safety can depend on that one’s will; because nobody must entrust himself to his opponent in a similar occasion.

The second method of gripping the sword is very forceful, due to the arrangement of the two fingers inside the incascio, and still the blade remains weak, because the hand does not stay entirely in its center, which is the grip, and placing two fingers inside the incascio, there remain only two others (and the weaker) on the grip; nor can they support it and guide it with that strength which is necessary in order to resist to the opponent’s impacts. Therefore, avoiding both extremes, he would grasp the sword with the whole grip in hand, and place only the index finger inside the incascio; he would let the thumb fall to rest over the tip of the index finger. So, he will come to grip the sword with a closed key, as my present illustration shows in letters, A, B and C.